He photographed sinking of carrier Yorktown

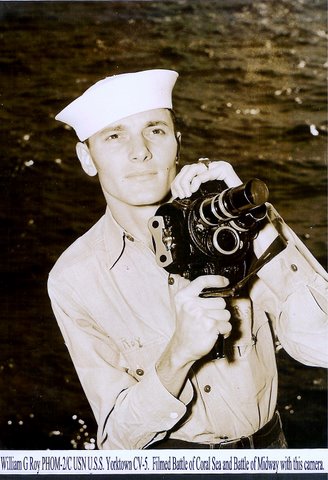

Bill Roy was a 21-year-old photographer’s mate aboard the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown when she was sunk by an enemy submarine at the Battle of Midway June 7, 1942.Midway was the defining battle in the Pacific Theater during the first six months of World War II. The United States went to war after its Pacific Fleet was bombed by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor on Dec, 7, 1941. At Midway the Americans sealed the fate of the Japanese Imperial Navy and ultimately stopped its westward expansion.

It began with the attack on the Yorktown June 4, 1942. It reached a climax the next day when three of the four Japanese carriers, Akagi, Kaga and Soryu, were sunk by a vastly inferior American fleet. The following day the badly damaged Hiryu, the fourth carrier, was also sent to the bottom by American air power. As a consequence, the momentum of the war in the Pacific switched in favor of Allied forces.

Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, the officer who planned the Pearl Harbor attack six months earlier, commanded the massive Japanese fleet at Midway.

Bill Roy was a kid who grew up in Lake City, Fla., along the Florida-Georgia border, in the 1930s. He graduated from high school in 1939 and went to sea.

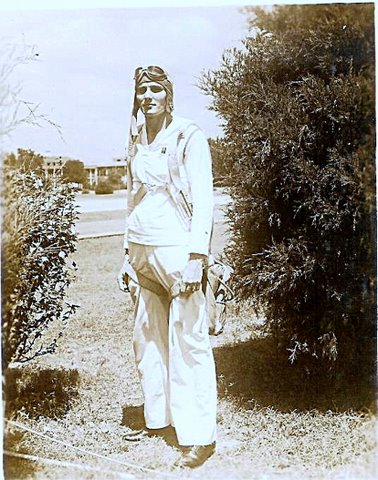

His first assignment aboard ship in 1940 was as a member of the engine room gang aboard the battleship USS Arkansas. Just before the start of World War II, he graduated from the Navy’s combat photographer’s school at Pensacola.

By November 1941, Roy had reported for duty aboard the Yorktown as one of the ship’s photographers. His job was to capture the daily activities aboard the Yorktown with a Speed Graphic still camera and Mitchell 35 millimeter movie camera. Shortly after he joined the Yorktown’s crew the carrier headed for the Hawaiian Islands.

By the time the Yorktown cleared the last lock on the Pacific end of the Panama Canal, Pearl Harbor had been bombed. A couple of enemy submarines were waiting for the carrier as she steamed into the open sea, protected by her battle group. She escaped the enemy subs unscathed. The carrier picked up a contingent of Marines in San Diego and headed for American Samoa where they were put ashore.

“In early January 1942 we sailed into Pearl Harbor. On the Yorktown you could hear a pin drop,” Roy recalled.

“Everyone on deck stood at attention and looked at the oil slick from our destroyed fleet covering the surface of the water in the harbor. The most solemn thing was the sight of bombed out and burned ships along Battleship Row.”

After re-provisioning, the Yorktown headed for the Marshall and Gilbert Islands in the South Pacific. Planes from the carrier attacked Japanese outposts on Juluit and Mali Islands in the Gilbert chain.

Bill Roy was not only a photographer aboard the carrier USS Yorktown, but he was also a member of the Salvage Party that returned to try and rescue the doomed ship.

The Yorktown also made three raids on Tulagi Island in the Solomons. The Japanese were trying to bring an invasion force into the Solomons. They were in the process of establishing a defensive perimeter in the South Pacific to deny American forces access to Australia. At the same time Japanese planes were bombing Port Darwin in Northern Australia in an attempt to soften it up for an eventual invasion.

A Japanese fleet defeated a British fleet at the Battle of the Java Straights. As a result, the Allies had no fleet protecting Australia from an assault by Japanese land forces transported by ship.

“We showed up (in the Coral Sea) with Task Force 17, Adm. Frank J. Fletcher in command. He also had the carrier Lexington,” Roy said. “We were kept informed of Japanese ship movement by Australian coast watchers. The Japanese had three carriers the Shoho, Zuikaku and the Shokikiu. They were providing air support for their attack on Allied forces at Tulagi and Port Moresby in the Solomon Islands.”

At 8 a.m. on May 7, 1942, search plans from the Yorktown spotted two Japanese carriers and four heavy cruisers in the Coral Sea. The carrier Lexington launched two fighters, 28 dive bombers and a dozen torpedo bombers against the enemy fleet 175 miles away, northeast of the Louisiade Island group. The Japanese carrier Shoho was sunk in the confrontation.

The next day the two fleets found each other, despite the fact they were out of sight of the sailors aboard ships. The Yorktown launched 24 bombers, six fighters and nine torpedo bombers. The Lexington put about the same number of planes in the air.

The carrier USS Yorktown is on fire after a Japanese bomb went down her smoke stack during the Battle of Midway on June 4, 1942. Photo by PhoM2/C Bill Roy

The best and most experienced fighter pilots the Japanese had, including some who had been involved in the Pearl Harbor attack, flew from the decks of the Shokaku and Zuikaku, heading for the Yorktown and Lexington.

The Japanese squadron beat up on Lexington. The Yorktown was also seriously damaged during the initial encounter with the enemy. The Lexington was on fire and about to explode from leaking aviation fuel vaporizing in storage tanks below deck. At 4 a.m. the carrier was dead in the water.

Adm. Fletcher, in command of the carrier fleet, decided to abandon the Lexington because it was a floating time bomb. At 6 a.m. the 1,200-man crew of the carrier transferred to waiting destroyers and cruisers circling near by.

The derelict Lexington was sunk by an American destroyer.

“I shot pictures of the Lexington being sunk from the bridge of the Yorktown,” Roy said. “I used a movie camera and an aerial camera with a telephoto lens to take the pictures.”

The Yorktown wasn‘t doing too well herself. She had been hit by a bomb from a Japanese dive-bomber that caused structural damage to the carrier and destroyed a number of compartments below deck. Capt. Elliott Buckmaster, the skipper, skillfully evaded eight torpedoes by maneuvering the ship straight ahead as the deadly metal fish passed harmlessly by on both sides of the Yorktown.

“The significance of the Battle of the Coral Sea was that it stopped the Japanese attempt to invade Australia and it also denied the enemy three carriers it would have had at Midway. The Shoho was sunk and the Shokaku and Zuikaku returned to Japan for repairs and missed the Battle of Midway. The Japanese also lost the cream of its naval air force,” Roy explained.

When the Yorktown reached Pearl Harbor, after the Battle of the Coral Sea, her refrigeration system was gone and she had extensive bomb damage. Repairs were expected to take at least 90 days before she could go to sea again.

Adm. Chester Nimitz, Naval commander in the Pacific, said, “You have 72 hours to repair the Yorktown. I need her.”

The USS Yorktown burns on June 4, 1942, after a Japanese bomber dropped a bomb down the smoke stack of the battered carrier. Photo by PhoM2/C Bill Roy

“Some 1,200 shipyard workers came aboard the carrier and the entire ship’s crew worked day and night fixing the Yorktown,” Roy said. “We went back to sea 72 hours later.”

It was the Doolittle Raid off the carrier USS Hornet that changed the thinking of the military command in Tokyo. In March of 1942 Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle and 16 B-25 Mitchell twin-engine bombers flew off the carrier on a bombing raid over Tokyo and several other Japanese cities. This was four months after Pearl Harbor was attacked.

Although the Doolittle Raid caused inconsequential damage, it resulted in the Japanese high command’s war planners placing more emphasis on defense.

By the time the Yorktown sailed out of Pearl Harbor on May 30, 1942, Adm. Yamamoto and his fleet of 160 ships were on the way to deliver the knockout punch. The American fleet at Midway totaled 76 vessels. Because the Americans had broken the Japanese naval code, they knew where the enemy fleet was headed, which was strategically significant.

On June 4, 1942, the Yorktown steamed 1,200 miles, from Pearl Harbor to a point northeast of Midway, when she was attacked by enemy dive bombers at 10:20 a.m. Three bombs penetrated the carrier extensively damaging the rebuilt ship.

“The first bomb hit near the Number 2 elevator, wiping out a 40 millimeter gun crew. The second bomb went down the stack and below deck, taking out the carrier’s boilers. The third bomb hit near the forward elevator, exploding on the fourth deck near the bomb, torpedo and aviation fuel storage areas,” Roy said “The Yorktown was dead in the water. Smoke was pouring from the ship, the wounded were being brought up on deck and they were trying to get the guns back in action.”

All the while, Roy was capturing the chaos aboard the Yorktown on film with his Graphic still and Mitchell movie cameras.

“They got the boilers on the Yorktown back on line and got the ship moving again. We were doing 20 knots when the Japanese torpedo planes attack the carrier,” he said. “Our fighters took off in the middle of the attack and shot down most of the enemy torpedo planes, but not before two torpedoes struck the Yorktown.

“They got the boilers on the Yorktown back on line and got the ship moving again. We were doing 20 knots when the Japanese torpedo planes attack the carrier,” he said. “Our fighters took off in the middle of the attack and shot down most of the enemy torpedo planes, but not before two torpedoes struck the Yorktown.

“The first torpedo hit directly in front of me on the port side amidships,” Roy said. “I was up on the signal bridge 50 feet above the deck taking pictures. The torpedo penetrated deep into the carrier. When it exploded, it rocked the ship and knocked me over. The second torpedo exploded on contact below and blew a hole in the ship’s port side.

“The Yorktown rolled hard to port and listed at a 28-degree angle. It was so far over, the hanger deck, where the planes are stored, was almost under water,” Roy said.

“The Yorktown rolled hard to port and listed at a 28-degree angle. It was so far over, the hanger deck, where the planes are stored, was almost under water,” Roy said.

At such an angle, it was difficult to walk on deck. Capt. Buckmaster surveyed the damage and decided the Yorktown might capsize. She was dead in the water once more and without power, so none of her guns were operational. He abandoned ship.

The 2,250 officers and sailors aboard the Yorktown went over the side. Roy was among those who took a swim.

“I had three cans of 35 millimeter movie film in watertight metal cans under my life preserver when I went over the side,” Roy said. “There were some ropes hanging over the side and a mess attendant who couldn’t swim was tangled in the lines. I untangled them and we jumped in the water together. I got him to a life raft.

“Everyone in the water was having difficulty breathing because of fumes from the bunker-C fuel oil from the ship covering the surface. Because of the wind and wave action we kept being blown into the ship,” he said. “Eventually a motor whaleboat came along and took us to the destroyer Hammann. I was exhausted and covered with black oil.”

The stern of the American destroyer USS Hammann points skyward on the way to the bottom. The photo was taken by Roy from the Yorktown. Photo by PhoM2/C Bill Roy

The next day Roy gave his three cans of movie film to a young photographer he knew who was aboard the heavy cruiser USS Astoria that came alongside the destroyer he was on to pick up the injured. On June 5, the following day, Capt. Buckmaster asked for volunteers to return to the Yorktown as a salvage party to try and save her and get her back to port. All together, 29 officers and 141 sailors volunteered.

“I was one of them. I felt it was my duty. I felt we could do it. I loved the ship,” Roy said as he told his story. “We made good progress the following day, putting out the fire in the forward part of the carrier. We cut away the 5-inch guns on the port side and pushed some planes over the side to help correct the list,” he said. “The destroyer Hammann was tied snugly to the starboard side of the carrier to supply the salvage crew with power and pumps.

Unexpectedly, the Yorktown was hit by three torpedoes from a Japanese submarine, I-168, that had been stalking the damaged ship for two days. The first torpedo struck the carrier under the bridge. The concussion from the impact ripped the Hammann in two, catapulting sailors into the sea.

Roy took three sequential shots of the Hammann’s stern going down with sailors clinging to the wreckage. When the destroyer’s back end reached a certain depth the 18 depth charges on her stern exploded causing more damage.

The final two torpedoes penetrated the Yorktown and exploded deep inside her. The carrier rolled hard, throwing member of the salvage party in all directions. Most of the 170-member salvage crew was taken off the Yorktown aboard the minesweeper USS Vero.

The Vero and several other ships circled the ill-fated carrier throughout the night. At 5:30 a.m. on June 7, 1942, it appeared the Yorktown had righted itself and was on an even keel, floating low in the water. Roy was shooting pictures of the ship with a movie camera and a Fairchild aerial camera.

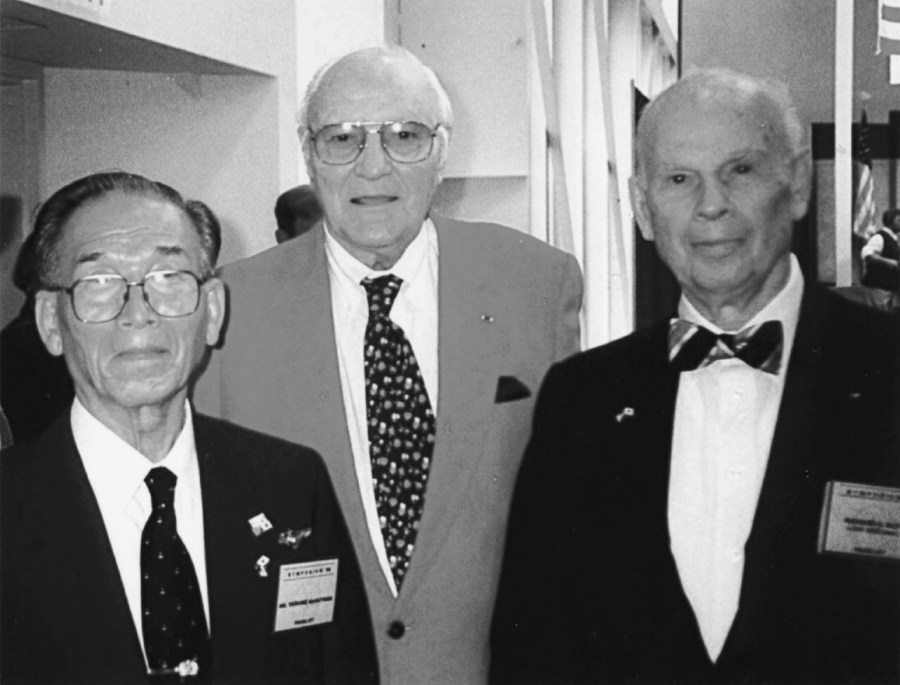

Taisuke Maruyama, a Japanese bomber pilot, torpedoed the Yorktown while flying off the carrier Hiryu. Bill Roy (center) was a U.S. Navy photographer who filmed the Battle of Midway and was part of the Yorktown’s salvage crew. Richard Best, was a dive bomber pilot who helped sink the Hiryu at Midway.

“Suddenly the Yorktown that had been floating dead in the water turned to port and rolled over with her battle flags flying. At 7:01 a.m., June 7, 1942, the ship settled stern first into the sea and disappeared,” Roy said.

He captured the final seconds of the USS Yorktown on film.

The Battle of Midway was over. The Japanese offense in the Pacific was also over with the loss of the four fleet carriers: Akagi, Kaga, Soryu and Hiryu. The heavy cruiser Nikuma and Mugami and the destroyers Asahjo and Tawskace and the ironclad Haruwa were also sunk. In addition 322 planes and 2,155 men were lost in the engagement.

The American fleet lost the Yorktown and the destroyer Hammann and 147 aircraft.

It had been a huge American victory. It resulted in Adm. Yamamoto’s fleet steaming away in defeat. A month later, the U.S. Marines landed at Guadalcanal. When the Leathernecks finished the job there they had stopped the enemy’s western movement for the first time on a Pacific island in World War II. It was the beginning of the end for the Japanese.

About the same time the Marines were winning the Battle of Guadalcanal, Photographer’s Mate 2/C Bill Roy was on liberty. While walking down Market Street in San Francisco he spotted the movie marquee in front of the Telenews One Hour Newsreel Theater. It read, “Yorktown Sunk at Midway.”

“I didn’t realize they were showing my movies. I had no idea,” he said with smile more than 60 years later.

Bill Roy’s commendation from Adm. Nimitz

“WILLIAM G. ROY, Photographer’s Mate 2nd Class, U.S. Navy, for service as set forth in the following COMMENDATION:

“For heroic conduct and meritorious service in the line of his profession as a member of the volunteer salvage crew which attempted on June 6, 1942, to salvage and return the USS YORKTOWN to port. Knowing full well that the YORKTOWN was in a precarious condition because of damage received in the battle on June 5, 1942, that she was barely seaworthy, and that she would probably be the target of repeated submarine and air attacks against which it would be very difficult to defend her, he requested that he be allowed to return to the ship and assist in her salvage. The effort of the salvage party were so successful that all remaining fires were out and two degrees of list had been removed when, in the mid-afternoon, the ship was struck by two torpedoes fired from an enemy submarine. His conduct was in accordance with the best traditions of the naval service.

“C.W. Nimitz, Admiral, U.S. Navy”

Roy’s File

Name: William G. Roy

Age: 84 (at time of interview 2002)

Hometown: Lake City, Fla.

Currently: Naples, Fla.

Entered Service September 23, 1939

Discharged: November 1948

Rank: Commander U.S. Navy

Unit: USS Yorktown CV-5, USS Arkansas BB-33

Commendations: Citation from Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, Commander Pacific Fleet

Married: Barbara DeBolt

Children: William G. Roy, Jr., Jan Roy and Lynn Roy

This story was first published in the Charlotte Sun newspaper, Port Charlotte, Florida and is republished with permission.

All rights reserved. This copyrighted material may not be republished without permission. Links are encouraged.

Click here to view the War Tales fan page on FaceBook.

William Glenn Roy, Sr.

William Glenn Roy, Sr., 95, passed away April 10, 2015 at his home. He was born on December 27, 1919 in Coaling, AL to Reverend Edward Roy and Sarah E. Roy. He lived the past 30 years in Naples, FL.

William Glenn Roy, Sr., 95, passed away April 10, 2015 at his home. He was born on December 27, 1919 in Coaling, AL to Reverend Edward Roy and Sarah E. Roy. He lived the past 30 years in Naples, FL.

Bill was preceded in death by his parents; as well as three brothers, Frank Roy, Paul Roy, and Charles Roy; three sisters, Roberta Roy Merry, Edwina Roy Hammond, and Eunice Roy Dorety.

He is survived by his wife, Barbara Herberg Roy, Naples, FL; two daughters, Jan (Jim) Cummings, Ft. Lauderdale, FL and Lynne Roy, Live Oak, FL; one son, William Glenn Roy Jr., Altamonte Springs, FL; four grandchildren, Kasey (DR) Cummings Repass, Jacksonville, FL; Mindy Cummings Nowakowski, Big Sky, MT; William G. Roy, III, Altamonte Springs, FL; Christopher Andrew (Jamie) Roy, Longwood, FL; five great-grandchildren, James Lee Repass, Robinson Mackay Repass, Ryleigh Cummings Repass, Hunter Joseph Nowakowski, Tucker James Nowakowski, and Camden James Roy. Five stepchildren also survive, Bill (Terri) Herberg, Mike (Chris) Herberg, Jenny Herberg, Cheri Herberg, and Steve Herberg; and three grandchildren, Stephanie, Hayley, and Kelsey.

Bill Roy served his country in World War 11 as a Navy photographer on the USS Yorktown, which was sunk in the Battle of Midway. He took historic combat photos and was a worldwide speaker on this battle. As a decorated veteran, he continued in the Naval Reserve and was a contracting manager for the Gemini, Titan 111, and Saturn-Apollo programs in the 1960s. He was a founding member of the Space Pioneers, in the NCMA Hall of Fame, a city commissioner, and an Outstanding Alumni of FIT. He also was a corporate attorney for Dow Chemical in Washington, DC and Midland, MI.

Bill will be remembered as an avid conversationalist, world traveler, and humanitarian. Bill and his wife, Barbara traveled around the world more than 14 times, making friends and helping those in need. He was a great ambassador for our country.

There will be a memorial service at the Naples United Church of Christ in Naples, FL on May 21st at 2:00 p.m. followed by a ‘Celebration of his Life’ at the NSYC. Interment will be in Lake City, FL, at Dee’s Funeral Home at 2:00 p.m., with a graveside service for family and friends following on April 20, 2015.

In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to the Guatemala Medical Clinic Project through the NUCCC, 5200 Crayton Road, Naples, FL 34103.

Fuller Funeral Home, Pine Ridge Road, in charge of arrangements.

– See more at: http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/naplesnews/obituary.aspx?pid=174627584#sthash.zPE8zV3m.dpuf

http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/naplesnews/obituary.aspx?pid=174627584

Reblogged this on Lest We Forget and commented:

One more example of War tales…

Reblogged this on pacificparatrooper and commented:

The photographs you’ve seen and know so well came from the heroism of this man!

Don,

Please write me a personal email

pierre1948@hotmail.com

Reblogged this on A Conservative Christian Man.

Really enjoyed this. It’s nice to see credit being given to the photographers who have captured history in the making. Bill Roy must be a very rich man by now with the royalties from all the archive films shown so often on Discovery Channel, History Channel, Discovery History Channel……

Reblogged this on The Missal.

Stories such as this of Bill Roy are so important and need to be shared as widely as possible. They tell of heroism and what brave people can do.

What courage and what presence of mind!

Incredible talent whose work will live forever.

Any link, please, to any of the surviving imagery?

Reblogged this on quirkywritingcorner and commented:

Impressive

What a story! These personal comments make Hollywood look like a picnic or lies.

, I notice that when he retired from the Navy he had attained therank of Commander, which is not a lowly rank and I’m curious to know more. How and when did he receive his first commision and in which branch of the service?

He certainly did tremendous work as a photographer, shooting wih a camera when I imagine at times he’d rather have been shooting with a gun. Many do not realize the importance of photographers in the present times and especially during warfare.

Back in the 1960’s betweeen 60 and 64 I had the pleasure of working with a man who had been a war time photographer ith the Australian Forces, he would never speak about what he saw and what he did; I think perhaps some of the work and memories still haunted him. He was what we call here “a good bloke”, He must be long dead now.

What a courage! Thank you for sharing this story.

Reblogged this on Plausibly Live and commented:

I was perusing Don’s site and I came across this one which I found absolutely fascinating…

My uncle, Donald W. Wilson, also received a commendation for the salvage attempt. https://joynealkidney.com/2017/06/05/a-citation-from-the-commander-in-chief/

A true U.S hero, a man amongst men.