Lily Marlene was the song they liked the best

Sgt. John Robinson was 20 years old and served with the 2nd Armored Division in World War II when this picture was taken. Photo provided

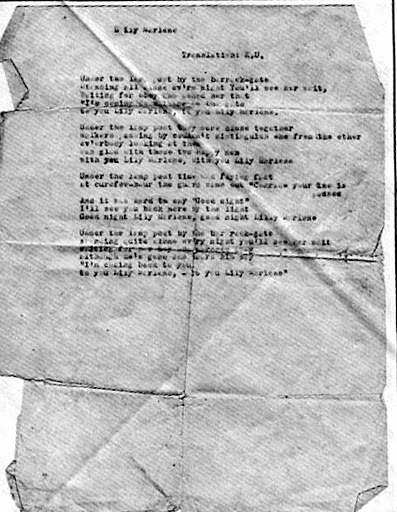

It was a voice from the past typed in blue on the sheet of yellowing copy paper that dropped from the little book about the 2nd Armored Division’s exploits in Europe during World War II.

“Lily Marlene Translation” is what it read at the top. The words to the poem became a wildly popular barracks ballad on both sides in the Second World War.

It concludes: “Under the lamp post by the barrack gate

standing quite alone every night you’ll see her wait

waiting for her boy who marched away

although he’s gone she heard him say,

“I’m coming back to you

to you Lily Marlene, to you Lily Marlene.”

John Robinson of Punta Gorda, Fla. a sergeant in the 2nd Armored Division who fought his way through North Africa, France, Holland and Germany during World War II, is the owner of the book that contained the poem. What’s it all about?

“By the time the war was over we were in Germany. We had liberated a little wind-up Victrola. We had a record of ‘Lily Marlene’ we played over and over, but it was in German,” he said. “Someone, I don’t remember who, translated it into English. I got a copy of the translation and put it in my 2nd Armored book. The German civilians got a kick out of us playing that song so much.

This is an English translation of ‘Lily Marlene,’ a popular song with soldiers on both sides during World War I and II. The men in John Robinson’s 2nd Armoured Division played the German version of the popular ballad continuously. Sun photo by Don Moore

“Under the lamp post by the barrack gate/Standing all alone every night you’ll see her wait…,” I still remember it,” he chuckled.

The war for Robinson began, “When we sailed from Staten Island, N.Y., on Nov. 2, 1942 and landed at Casablanca, Morocco in North Africa on Nov. 18.

It wasn’t until their unit reached Tunisia and the Kasserine Pass months later that they suffered any serious casualties.

“All I remember is that ownership of that pass changed hands between us and the Germans four or five times in a week,” he said. “We finally ended up with it.”

By October 1943, the German North Afrika Korps had fallen back to the shore of the Mediterranean Sea. It escaped to Sicily by ship. Robinson and the 2nd Armored headed for England to start preparations for the Normandy Invasion more than six months away.

“We landed at Liverpool, England and moved to a little town named Andover outside London. We conducted tank maneuvers on the Salisbury Plains until June 1944 when we boarded an LST (cargo ship) for Normandy,” he said.

“On D-Day plus 2 we landed. It was bad,” Robinson recalled. “There were dead American soldiers all over the beach and floating in the water. Personal equipment was scattered everywhere. Our front line was not more than a mile inland. They were fighting hedgerow to hedgerow.”

Robinson had a .50-caliber machine gun, and he and a buddy anchored a section of hedgerow until the 2nd Armored’s tanks moved up. Every field in this part of France was bordered by hedges. The Sherman tanks were pretty useless in the hedgerows until someone in the division welded a couple of pointed steel plates onto the front of a tank. That enabled the Americans to push their tanks through the bushes and fight their way out of the hedges a few days later.

“The German air force hit us with anti-personnel bombs at night. They were little sticks with knobs on one end. These cluster bombs would spray out of a canister in the air and cover the place every six feet,” he said.

One night his unit saw three killed and 17 wounded from these bombs.

After fighting its way through the hedgerows the 2nd Armored held up for about three weeks waiting for supplies and additional troops to catch up. Then the combined Allied forces began to break through the German line holding the Cherbourg Peninsula.

“One morning here came an umbrella of planes flying over from England. They were sent over to bomb the Germans at St. Lo,” Robinson said. “They really laid it on them. At 2 p.m. the bombing stopped just like that.”

It was July 28, 1944.

The Infantry division that was accompanying the 2nd Armored was out front holding the line. The plan was that the infantry would put down a smokescreen and the bombers would bomb the enemy just beyond the screen.

“A puff of rain came and drifted the smokescreen back over the American lines,” he said. “As a result, a bunch of our infantry got bombed. I saw bomb craters as big as this room and lots of American bodies.”

The 2nd Armored had to move forward, despite heavy losses suffered by the infantry regiment accompanying the mechanized unit. As they moved forward, they passed knocked out German tanks and trucks attacked by American P-47 Thunderbolt dive bombers and P-51 Mustang fighter planes.

“The Germans were ducking and eventually they started retreating. We entered St. Lo without resistance. Then we chased them all the way across France in about six weeks,” he said.

It wasn’t until the 2nd reached Vaals, Holland, that the enemy toughened up.

“We had two or three days of heavy fighting around Baals, but we continued to push the Germans back,” Robinson recalled. “We reached the Siegfried Line. We drove right down the road with our tanks through the line without meeting resistance,” he said.

American forces were rolling through Germany facing little enemy opposition until late December 1944 when the enemy made its final offensive thrust in the Ardennes at the Battle of the Bulge.”

“We were in Aachen, Germany when we received a distress call and had to drop back at least 100 miles as quickly as possible, all the way to Bastogne. We drove from 6 a.m. to right about sundown and attacked in force in the snow and cold when we arrived,” Robinson said.

“We hit the Germans on their north flank near a little town called Huy. Those civilians in Huy were tickled to death we saved their town from the enemy. They couldn’t do enough for us,” he said.

The 2nd Armored stopped its advance and held in place. A few days later it was taken out of the line for a little R and R in a plush roadhouse. A couple of days later it was sent back to Aachen to continue its drive across Germany.

They crossed the fabled Rhine River on a pontoon bridge assembled by the engineers and continued their advance into the heart of Germany.

“We were moving east as fast as we could along the road and encountering little opposition,” he said. “German soldiers were walking west in single file for miles on either side of the road with their hands over their heads. It was January or February of 1945 and they had given up.”

The 2nd Armored reached the Elbe River at Magdeburg. It sent a contingent from the 41st Armored Infantry Regiment across the river before the Russian’s arrived.

“They got the cotton shot out of them by the Germans. The 41st had to pull back to our side of the river. We waited for the Russians to reach the far side of the river two or three days later,” Robinson said.

When advance units of the Russian army reached the Allied side of the Elbe, they were in a partying mood. They wanted to barter, particularly for American watches and pocket knives.

It was early May and the war in Europe would end in several days.

Robinson had accrued 127 going-home points. An American soldier needed at least 73 points to get on a ship headed for the U.S.A.

He sailed from Camp Lucky Strike, an American debarkation camp in Le Havre, France. He arrived in Boston in late September of 1945.

“When we walked off the boat in Boston there were dozens of steam locomotives in a nearby railroad yard blowing their whistles in unison to welcome us home,” he recalled. “It was really something.”

On Oct. 12, 1945, Lucille, the girl he left behind, was waiting for him at the Greyhound Bus Station in Cincinnati, Ohio.

“We got married immediately and I bought a house right away with the money I had accumulated while in the Army,” Robinson said. “Jobs were hard to get, so I went to work in a Cincinnati restaurant.”

Several years later he opened his own restaurant, “Johnny’s Restaurant.” His most successful location was in the Textile Building at the corner of Fourth and Elm.

Robinson sits at his dining room table covered with memorabilia from World War II. Sun photo by Don Moore

For forty years, until he and Lucille moved to the Punta Gorda area in 1987, they were in the restaurant business.

“Two years ago Lucille passed away,” he said softly with downcast eyes. “I miss her alot.”

Despite his loss and his 82 years, Robinson hasn’t let his troubles or his age get him down.

“I thought I’d retire when I moved down here. But I saw these old guys working in Publix in Punta Gorda. I went over there and got a job. In about two weeks I will have worked there 14 years.

“It’s wonderful working for Publix. I’d hesitate quitting even if I died,” Robinson said with a grin.

Robinson’s commendations

John Robinson of Punta Gorda received five bronze battle stars for participating in five major battles: Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Central Europe and the Ardennes (the Battle of the Bulge). He also received the American Defense Medal, Good Conduct Medal and the Belgium Fourraguere.

Lili Marlene’s history

In 1915, Gardefusilier Hans Leip wrote a farewell poem for his two girl friends, Lili and Marleen. Shortly before World War I, it was set to music by Norbert Schultze. In 1938 it became the signature song of Lala Anderson, a Swedish singer. But it didn’t become popular with German soldiers until Rommel’s Afrika Korps began listening to it over the radio. It quickly spread to the English 8th Army and the American 1st Army. By the end of the war, it was the most popular World War II song. It’s believed to have been translated into 48 languages, according to information from the Internet.

This story was first published in the Charlotte Sun newspaper, Port Charlotte, Florida on Tuesday, July 20, 2001 and is republished with permission.

All rights reserved. This copyrighted material may not be republished without permission. Links are encouraged.

Click here to view the War Tales fan page on FaceBook.

I have always loved this song, no matter who has sung it, in English or German. It’s a classic and a wonderful tie to this hero’s journey through Europe during WW2. Thank you, deeply, for your service Mr. John Robinson.