Little known World War II surrender signed

Pvt. Ed Myslivecek at 18 shortly after completing boot camp at Camp Upton, Long Island, N.Y. in 1942.

Despite what you may have read in history books or seen on the History Channel, the Japanese at the close of World War II surrendered first on Ie Shima Island before surrendering to Gen. Douglas MacArthur aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

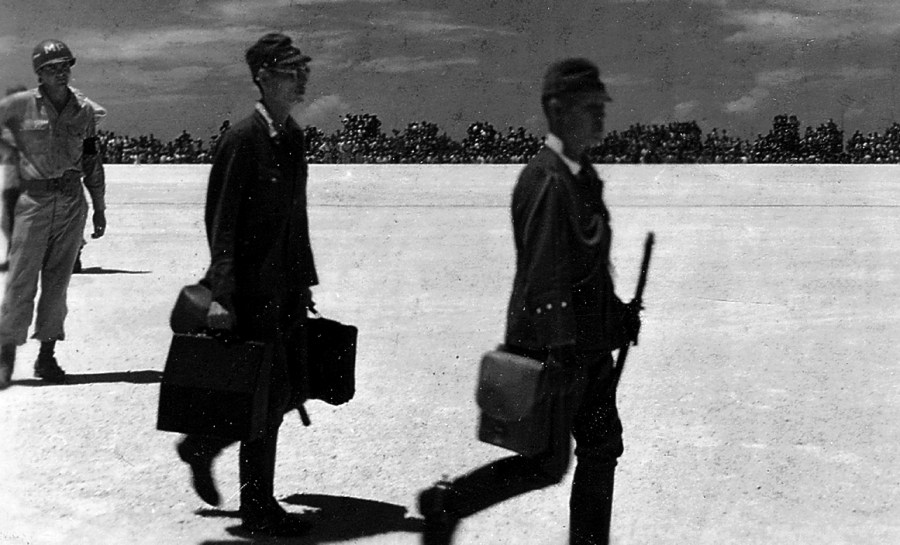

The unconditional surrender was initially signed on Ie Shima Island off Okinawa by Lt. Gen. Torasirou Kawabe, the vice chief of the Japanese Army’s General Staff, a few days earlier.

Ed Myslivecek of Venice, Fla. captured the event on film. He was a 22-year old aircraft mechanic and MP assigned to the 35th Fighter Group of the 5th Air Force in the Pacific.

“While I was there working as perimeter guard at the airstrip on Ie Shima Island, off the north tip of Okinawa, we heard that a group of high-ranking Japanese officers would be flying into the island as an advance surrender party,” said Myslivecek. “They arrived in three Betty twin-engine bombers painted white with three crosses on their wings, fuselage and tail, as ordered by the Americans.

“American P-38 Lightning fighters and B-25 Mitchell bomber escorted them into the field because we had no idea what they were going to do,” he said. “The fact they were going to surrender didn’t necessarily mean anything.

Lt. Gen Torasirou Kawabe, vice chief of the Japanese Army’s General Staff, with his Samuri sword in hand, walks across the tarmac at Ie Shima Island followed by his aide, after signing the preliminary World War II surrender document in late August 1945. This is the initial surrender most people know nothing about. Sgt. Ed Myslivecek of Venice, Fla. took the picture while serving as a guard on the island at the close of the war.

“They landed in the late morning, and Lt. Gen. Kawabe signed the preliminary surrender document. It must have been around Aug. 25, 1945. The Japanese got off their bombers with their satchels in hand and were immediately surrounded by an American delegation that was waiting for them on the runway.”

Kawabe signed the preliminary surrender document and then the whole contingent climbed aboard an American C-54 transport and flew on to meet with MacArthur who was in Manila in the Philippines.

In the almost 60 years since the preliminary surrender on the island off Okinawa, Myslivecek says he has never heard anyone mention the three-bomber Japanese fly-in. No one seems to know a thing about the incident.

All the world recalls is the formal surrender ceremony aboard the “Mighty Mo” in Tokyo Harbor on Sept.2, 1945. With a huge fleet of Allied bombers and fighters in the sky and scores of Allied ships anchored in the bay, MacArthur and his lieutenants were on the foredeck of the battleship. They signed the official surrender document with Japanese military and civilian leaders while thousands of American sailors watched from every perch on the Missouri.

Ed Mysliveck is pictured atop a P-47 Thunderbolt fighter plane while working on its engine on Morat Island, New Guinea in December 1944. Photo provided

Myslivecek’s Pacific odyssey began in early 1943 when he was drafted while working as a 20-year-old airplane mechanic for Republic Aviation. After basic training he went to the Pacific Theater of Operation.

“We spent 23 rough days aboard a ship and never saw land once. When I came ashore in British New Guinea, I swore I would never get on a ship again,” he said. “Much of the time, instead of being an airplane mechanic, I was put on guard duty.”

For months he and his unit went island hopping with MacArthur across the Pacific. Myslivecek’s unit was one of the ones left behind to subdue the enemy soldiers still on one Pacific island while the general and his front-line troops moved on to attack another island.

They took a pounding from Japanese Betty bombers at Hollandia Island in Dutch New Guinea. Eventually they overcame their opposition. His unit wound up at Luzon and invaded the Philippines with MacArthur.

“Going into Luzon we were attacked by kamikazes. On an LST (ship) all we had for armament were 20 and 40 millimeter anti-aircraft guns, which weren’t much,” he said. “We lost more men on LSTs and other troop ships from falling shrapnel than suicide Japanese pilots.

“Going into Luzon we were attacked by kamikazes. On an LST (ship) all we had for armament were 20 and 40 millimeter anti-aircraft guns, which weren’t much,” he said. “We lost more men on LSTs and other troop ships from falling shrapnel than suicide Japanese pilots.

“Every shell that goes up in the air has to come down somewhere,” He said. “With 200 ships all shooting up in the air, the shrapnel coming down is unbelievable.

“We went in on day one and fought the Japanese all the way to Manila. I was there when the Americans took over the prison in Manila where some of the soldiers who were on the Bataan Death March were kept,” Myslivecek said.

For several months he stayed in Manila while making preparations to move on to Okinawa. When they reached Okinawa, the American fleet spread across the ocean for as far as the eye could see.

After the initial surrender document was signed on Ie Shima Island near Okinawa, Mysliveck’s unit pushed on northeast toward the Japanese main islands. They had no idea what their reception would be when they reached Japan, but they were preparing for a hostile landing.

“I was amazed. The moment we hit the Japanese shore and met our first Japanese civilians they bowed to us,” Myslivecek said. “They were very courteous. It made you wonder if there had ever been a war on at all.”

The first base of operation was an airfield just outside Yokohama. From there, Myslivecek and his unit moved on to Tokyo. There was little left of Japan’s major city thanks to the efforts of the Army Air Corps.

Myslivecek spent the next several months being part of a cleanup detail.

“I was given an Army truck and 20 Japanese workers to start cleaning up the roads. They couldn’t speak English and I couldn’t speak Japanese, but we communicated,” He said. “They were very cooperative and very pleased that we were helping them rebuild their country.”

By December 1945, Myslivecek had accrued enough points to come home. The services had a system whereby soldiers returned to the United States after the war based on the number of service points they had.

After discharge from the military, Myslivecek took advantage of the G.I Bill, like millions of other returning GIs, and went to college. He became a high school teacher and taught architectural and engineering drawing in Babylon High School and Garden City High on Long Island, N.Y.

Myslivecek looks several pages of occupation money he collected WWII in the Pacific Islands. Sun photo by Don Moore

Considering World War II after more than half a century he said, “It was a necessary war. We were fortunate to have the leaders we had at the time we had them –people like Eisenhower, MacArthur and Patton were perfect for the jobs they were required to perform.

“As for the troops in the ranks, most of us had never been more than a couple of blocks from home until we joined the service. Everybody did their job and luckily it turned out well for us.”

Myslivecek’s File

Name: Edward M. Myslivecek

Name: Edward M. Myslivecek

Age: 80

Hometown: East Patchogue, Long Island, N.Y.

Currently: Venice, Fla.

Entered Service: November 1942

Discharged: January 1946

Unit: 35th Fighter Group, 5th Air Force

Commendations: Five battle stars for five major battles: Invasion of Philippines, Okinawa, New Guinea, Hollandia and Moretia

Married: Teresa Collings (deceased)

Children: Catherine Ann Marco, Marie Gallay, Edward, Barbara Coltas and Margaret McCasalin

This story was first printed in the Charlotte Sun newspaper, Port Charlotte, Fla. on Sunday, Aug. 25, 2002 and is republished with permission.

All rights reserved. This copyrighted material may not be republished without permission. Links are encouraged.

Click here to view the War Tales fan page on FaceBook.

My grandfather was at this surrender and took quite a few official photos that I now have in my possession. I’m currently scanning them and hoping to upload to WWII sites.

I was stationed on Okinawa at the time of the preliminary signing of the Peace treaty. I have pictures of the delegation, Betsie bomers and C-54 used to fly on to Manial,where they meet with MacArthur -John E Lochner

johnelochner@charter.net

John, Where do you live and what kind of pictures do you have? Don Moore War Tales Sun Newspapers

Don,

just caught up with your post, have pictures of the delegation and planes. I was in the 341st air drone squadron. Our p-51 was on e-ishims. I live at 441 Eaton village trace Lenoir city tn 37771

Where do you live?

John,

I live in North Port, Fla.

Don Moore

War Tales

Sun Newspapers

My Grandfather Benito Garza was also at I E Shima. He stated a white horse was also on board. Is it true it was the Japanese Emperor’s horse?

Does anybody remember a Joe Dobbins from Washington State at Ie Shima ? He was a member of the 35th fighter group.

My father, Jack Owings, was on le Shima during the surrender. He was a waist gunner in a B-24 bomber in the 64th Bombardment Squadron…looking for somebody who might have known him. He took pictures of the surrender and sent them home, but the pictures never made it home.

Thanks for posting this article. On this anniversary of the battle of Ie Shima, I was doing a search of Ie Shima items and came across it. My father was killed on that island on June 20, two months after the battle. He was an engineer in charge of a unit that built and maintained air strips, and not part of any fighting operation. But a bomber unexpectedly flew over the island and one of the bombs caught my father. I find these historical accounts quite interesting.

My father was there with you. I have his photos. I would love to contact you.

We’re not sure Ed is following War Tales. If you google his name or use zabasearch.com you probably can find him. Remember tho, Ed was 80 when this interview was published in 2002.

From Roy Russell. To Pat Bezdek: I was in Korea. The military censored mail from war zones. Your dad’s pictures were probably confiscated.

My father was stationed on Ie Shima as a ball turret gunner and I have the pictures that he took of the Japanese delegation planes on the tarmac. I also have his pic of the original Ernie Pyle memorial from 1945 and a pic of the current memorial that is there from when I was stationed in Okinawa in 1991. So much interesting history there.