Marine Pfc. Frank Garcia attacked in first wave at Iwo Jima

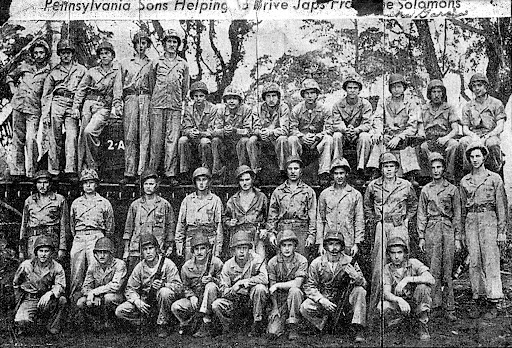

Pfc. Frank Garcia is pictured in the back row, second from the right in this Philadelphia Bulletin newspaper published during World War II. Photo provided

A week after the Japanese bombed the Pacific Fleet based at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on Dec. 7, 1941, dragging the United States into World War II, Frank Garcia joined the U.S. Marine Corps.

It would be the beginning of a 21 year career for the 19-year-old “Leatherneck” from Philadelphia, Pa. He would retire from the Corps in 1963 as a gunnery sergeant who had seen action in some of the biggest battles in the Pacific during the Second World War I.

After boot camp at Parris Island, S. C., Garcia wound up at the Marines’ advance training base at New River, N.C., as a member of Company B, 3rd Amphibious Tractor Battalion. Eventually he would become an “Alligator” driver.

Alligators were open troop carriers capable of navigation on land or sea. They were designed to take a couple of dozen fully-equipped Marines ashore from landing crafts anchored off the invasion beach and deposit them above the vegetation line.

The contraptions looked something like tanks with open cockpits to carry invading Marines and their crews. They were lightly armed with two .30-caliber machine-guns for use by each driver and his assistant.

Alligator vehicles were powered by a Cadillac engine. They crept along slowly both in the water and on land. Treads with fins moved the Alligators on land and sea.

In February 1943 Garcia’s unit shipped overseas to New Zealand and on to Bougainville, in the Solomon Island chain. November 1943 was the first invasion he took part in as an “Alligator” crewman.

“It was rainy season and the island was a mess of mud,” Garcia recalled. “There were no roads on Bougainville and you couldn’t move a truck. Our ‘Alligators’ were the only transportation moving on the island until Seabees got there and started building roads.

“Once we landed we were strictly used as supply vehicles for the rest of the campaign,” he said. “The 80 year-old North Port resident said he survived the engagement without a scratch.”

He wouldn’t be that lucky on Guam.

“We left Guadalcanal on May 17, 1944 on the damn LST (Landing Ship Tank) and sailed for 62 days before we got off at Guam,” Garcia said. “We had more time on the ship than some of the sailors that brought us in as replacements. We were going stir-crazy.”

Guam took the Marines about a month to secure. The jungle on the island was so dense that Japanese soldiers were still coming out of the bush 40 years later not realizing the war had been over for decades.

“I was on the beach at Guam driving an ‘Alligator’ when I got injured. Me and a kid from West Virginia were parked. The troops had all piled off and he was throwing their gear off when an enemy artillery or mortar shell hit. It blew a 3-foot hole underneath the front of our tractor,” Garcia said.

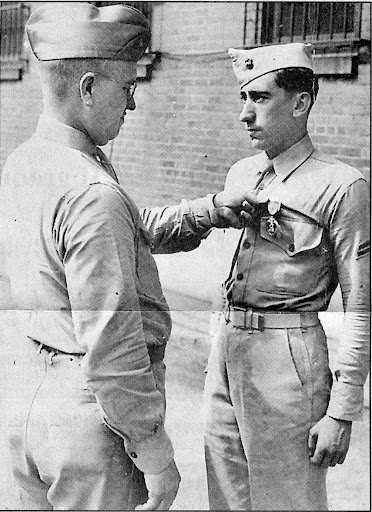

Cpl. Garcia is awarded the Purple Heart by Col. William H. Hollingsworth for injuries he received in the invasion of Guam during World War II. Photo provided

“I was bent over yelling at the kid to get the stuff off the ‘Alligator’ so we could get the hell off the beach when the round exploded. If I had been sitting up straight, the shrapnel from the shell would have taken my head off.

“Most of the explosion went over my head and hit him. I got a bunch of pinpoint shrapnel in my arm, neck and the side of my face that wasn’t serious and worked its way out later.

“But my crewman was hit right in the face with a piece of shrapnel as big as my fist. He was lying face down. I jumped in the back of the tractor and rolled him over, but he had no face. I knew he was dead.

“The kid had just joined the company when he was assigned to my vehicles as a crewman. To this day, I can’t understand why it wasn’t me who was killed,” he said. “I guess it wasn’t my time.”

Garcia was in the first wave of landing crafts at Iwo Jima on D-Day, Feb. 19, 1945, that hit ‘Blue Beach’ on the far right side of the landing area with the 4th Marine Division. Iwo Jima was the bloodiest engagement acre-for-acre that the U.S. Marine Corps took part in during World War II.

When the shooting stopped on Iwo, 6,821 U.S. Marines had been killed and 19,030 were wounded during the 36-day battle. An additional 22,000 Japanese soldiers were killed on the eight-square mile island. Only 1,081 enemy soldiers survived the battle.

Of the 16 million U.S. service personnel under arms during the 1,364 days that encompassed WW II for the U.S., 353 received the Medal of Honor, this nation’s highest military decoration for action “above and beyond the call of duty.” Of those medals presented, 27 were awarded for action at Iwo Jima–13 posthumously.

Garcia, by this time, had been transferred to the 2nd Armored Amphibious Tractor Battalion. This unit took such a beating earlier, during the invasion of Saipan, it need more experienced drivers for the “Water Buffalo” –amphibious tank-like vehicles. Instead of carrying troops ashore, like the “Alligators,” the “Buffaloes” had a crew of four and were equipped with a .75 mm howitzer and two .30-caliber machine-guns. They were used like amphibious tanks.

“They bombed Iwo Jima for 74 days before we attacked,” Garcia said. “the Navy and Air Corps hit the island with everything they had; it was going to be a three-day job is what hey told us.We knew better than that after Saipan, Tinian and Peleliu.

“The Japanese on Iwo Jima were 60 feet underground in concrete tunnels with 3-foot-thick walls that traversed the hole length of the island, from Mount Suribachi on the south to Kitano Point on the north end of the island.”

The bombardment by the American fleet and its supporting air power did almost nothing to damage the Japanese defense on the island. Lt. Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi, commander of the enemy forces, had an unpleasant surprise waiting for the U.S. Marines when they landed on the island’s black volcanic beaches.

On Feb. 19, Garcia and his armored tractor battalion were in an LST transport ship–affectionately called a “Large Slow Target” –anchored off shore a couple of miles.

“At 4 a.m. we were watching the fireworks on the horizon. The Army Air Corps, Navy and Marines had been bombing the island for days. The whole place should have sunk by now,” he recalled. “We were scheduled to land about 9 a.m. on Iwo Jima followed closely by the Marines in Amtraks and Higgins Boats.”

Their ship’s huge bow doors swung open shortly after daylight and the disembarking ramp was slowly lowered into place. It’s tricky business getting a heavy ‘Buffalo’ down a steel incline ramp into the sea.

“When you feel your treads bite into the water, at the bottom of the ramp, you goose it and it takes off,” Garcia explained. “We rendezvoused and circled the ship, in our ‘Buffalos’ unit they called us all up to the line of departure. Our armored amphibious vehicles were in the first wave to land on Iwo Jima. Our job was to go ahead of the Marines and bombard the breach with .75 mm cannon and sweep the area with machine-gun fire.

“We hit the beach at 9:01 a.m., right on time. There was almost no resistance. There were a few ‘pings’ from small arms fire hitting our ‘Buffalos,’ but nothing much,” he said. “The way Gen. Kuribayashi planned it, he waited until several waves of Marines were ashore before he let go with his guns.”

The Japanese general spoke fluent English. As a 37-year-old Army captain in 1928, he served as deputy military attache at the Japanese embassy in Washington, D. C., a decade before the war Kuribayashi attended the U.S. Army Cavalry School at Fort Bliss, Texas during this period to learn Horse-mounted combat.”

Looking through a small slit in the front of his armored vehicle, Garcia could see a 15-foot-high terrace of black volcanic sand his ‘Buffalo” would have to climb before going farther inland to take on the dug-in Japanese. His unit was lined up in front of the ridge of sand along the water’s edge.

“Word came down for us to climb over the terrace of ash and procured inland. But I couldn’t get any traction in the volcanic ash that formed the barrier. I couldn’t move upward. I was just spinning my tracks. All our vehicles were stuck in the black sand,” he said.

This is a “Water Buffalo”, an amphibious track vehicle with a .75 mm Howitzer in its turret, is like the one Garcia drove at Iwo Jima. Photo provided

They weren’t going anywhere. The ‘”Buffaloes” of the 2nd Armored Amphibious Battalion were reduced to firing their .75 mm howitzers over the sand embankment at an unseen enemy that wasn’t returning fire. Even the Marines landing in boats and coming ashore on foot a few minutes later had trouble slogging heir way through the coarse, black volcanic ash that comprised “Blue Beach”.

“By 10 a.m., thousands of Marines were ashore. It was mass confusion on the beach. Everything was bogged down in the sand. Then the Japanese cut lose with everything they had–artillery, mortars and machine-guns. The beach was so damn small they couldn’t miss.

“As far as our Marines were concerned it was mass murder. I guess that’s what you could call what happened to them that morning on the beach at Iwo Jima,” Garcia said.

Four days later he and his “Buffalo” were still stuck at the water’s edge firing at an unseen enemy farther inland. By this time they had moved to the far north end of “Blue Beach” where the terrace was a little lower and they had a better field of fire.

“We were down on the north end of the beach when the flag went up,” Garcia recalled. “There was a rumor that something was going to happen on the mountain about a mile or so away. When the 40-man patrol started going up Suribachi to put up the American flag, it was eerily quiet. They were expecting all hell to break lose, but they encountered little enemy resistance.

“When the first flag went up atop Suribachi everything on the beach sort of stopped. I recall that people were cheering and whistling when they saw the flag. Ships’ whistles offshore were also sounding.”

Marine Gen. H. M. “Howling Mad’ Smith, commander of the Marine invasion force at Iwo Jima, was watching the flag-raising with Secretary of War Frank Knox aboard a ship offshore. The secretary turned to the general after witnessing the “Stars and Stripes” being raised atop Suribachi and said, ‘That flag raising ensures the Marine Corps for the next 500 years.'”

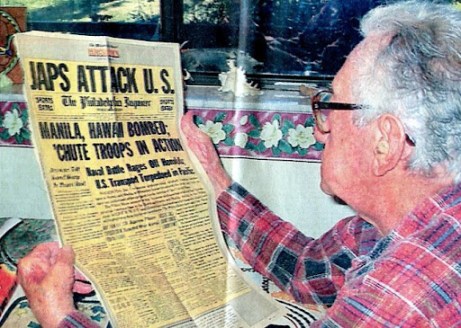

Frank Garcia of North Port, Fla. looks at a reproduction of the front page of the Philadelphia Inquirer for Dec. 8, 1941. He joined the Marines about a week after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Sun photo by Don Moore

For Marine Pfc. Frank Garcia retelling his Iwo Jima story 60 years later, it was a much more solemn recollection.

“Iwo Jima was such a small place. So many died. There were so many damn casualties,” he said softly as he closed his eyes tightly and bowed his head.

This story was first published in the Charlotte Sun newspaper, Port Charlotte, Fla. on Monday, March 3, 2003 and is republished with permission.

All rights reserved. This copyrighted material may not be republished without permission. Links are encouraged.

Click here to view the War Tales fan page on FaceBook.

Click here to search Veterans Records and to obtain information on retrieving lost commendations.

Thank you for sharing and therefore preserving his story. Thanks to him for his service.

Thank you for sharing the link to Garcia’s story.

Hi,Frank Garcia! I’m wondering if you was at Hawaii the island of Oahu in 1949?

I was wondering if you had any information on frank Garcia’s family. I have a very important item that belongs to mr. Garcia and should be given to his family.

My uncle Frank San Miguel was killed at Iwo Jima.