Dutch Underground rescued B-17 crew

This was 2nd Lt. Leonard Pogue when he was in his early 20s flying as a bombardier in the 8th Air Force in Europe during World War II.

Second Lt. Leonard Pogue knew he and the other eight members of his B-17 bomber crew were in for a bad day when they were informed of their target.

For the second day in a row, the crew of “Straighten Up and Fly Right” was ordered, along with the rest of the 493rd Bomb Group, 863rd Bomb Squadron, 8th Air Force, to bomb the ball-bearing plants and synthetic oil refineries around Merseburg, Germany. It was a harrowing assignment even though the 8th Air Force put 1,200 heavy bombers, escorted to the target by 650 fighter planes, in the air that day during World War II.

It was a six-hour round trip flight into the heart of Nazi Germany. The worst of the flight came during the final minutes on their approach to the target. Flying at 28,000 feet, the mighty armada of thin, aluminum-skinned, four-engine bombers droned ever so slowly toward their target. They flew through hail of deadly black puffs of flak from German antiaircraft guns far below. Flak from enemy guns could tear a bomber apart or rip the heart out of an aviator. The crew of Pogue’s “Flying Fortress” crossed their fingers and prayed.

“We were attacked by jet fighters that flew right through our formation. Our gunners were screaming, ‘I can’t get on them. They’re flying too fast for my guns to bear!’

“Our electric gun turrets on the top, bottom, nose and tail wouldn’t track fast enough to catch the German jets. Only the waist gunners on both side of the plane had half a chance to shoot down the jets, because they aimed their .50-caliber machine-guns themselves,” he said.

“We were getting hit bad. Everything in our B-17 was being shot up. Our ball-turret gunner got hit in the knee. We had to pull him out of his turret.

“Then we lost our number three engine. We were pulling half manifold pressure on our other three engines. We tied to feather the prop on number three, the inside engine on the right. It didn’t work, and it started windmilling out of control.

“As the bombardier, I was in the nose of the plane. I knew if the prop came off it could come right through where I was. There was no place to go so you stayed put,” Pogue said.

“We were losing altitude and air speed. We ended up dropping out of formation. One of last fighters flew by and gave us an ol’ “wing-wag” as he headed toward home. We were all alone. We were getting to an altitude where we could almost read the numbers on the houses below. By the time we had thrown everything out of the airplane we could to lighten the load hoping we’d get back to base.

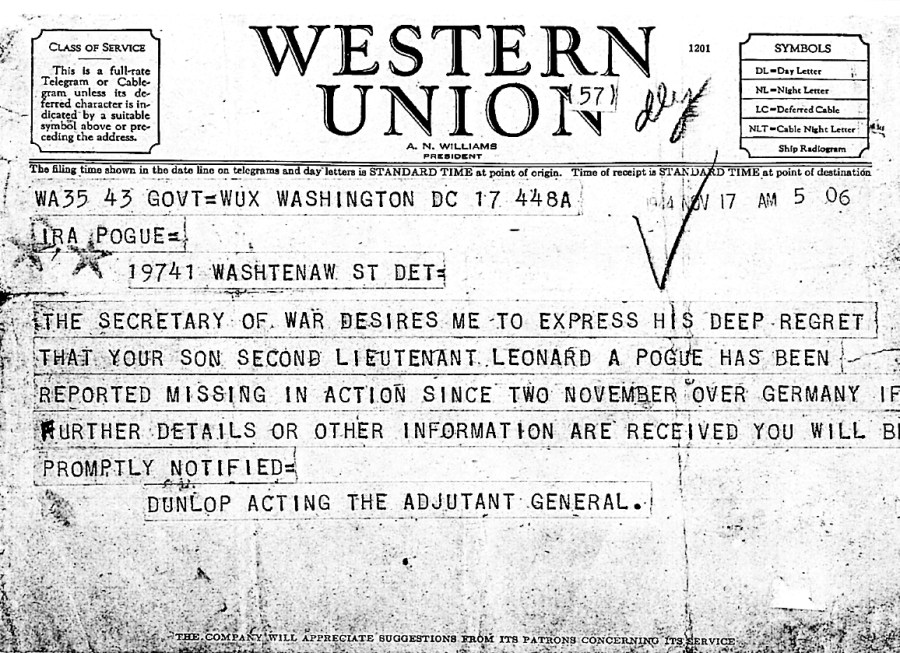

This is the telegram Leonard Pogue’s wife, Millie, received Nov. 17, 1944. She wasn’t told until almost the end of World War II that he had survived the crash of his “Flying Fortress” and was in the care of the Dutch Underground.

“It became apparent we weren’t gonna make it. The pilot was flying on one good engine and one that was pulling half manifold pressure. The other two engines were out.

“The pilot called for us to get into a ditching position. That meant everyone but the pilot and copilot went into the radio room and laid flat on the floor. I laid with my back to the wall and cradled the injured ball-turret gunner. The pilot expected to ditch the plane in the North Sea.

“We fell short of the sea and wound up in a cow pasture in Nazi-occupied Holland. We did a wheels-up crash-landing that jarred my backbone so hard I thought it was coming through my head. We all piled out of the plane after it hit the ground. I was the last one out because I had to take care of the injured gunner.”

The crew of “Straighten Up and Fly Right” was lucky. Dutch people from a nearby village arrived at the crash scene five minutes before German soldiers showed up.

“The first thing we had to do was get out of our uniforms,” Pogue said. “We stripped down to our long johns as the people from the village threw clothes at us. We dressed like the farmers in the village and were told to run across the field to a nearby farm beside a lake. We were to hide behind the barn and stay there until someone came for us.

“By this time, Germans were almost on top of us. Everybody had run off except for me and the ball-turret gunner, who couldn’t run because of his injured knee. I could see I wasn’t going to be able to help him, so I told our gunner, ‘I’ve got to go.’ I took off running toward the farm, too,” Pogue said.

“I could see our navigator’s red head way in front of me bobbing up and down as I ran. I ran in his direction as the Germans kept yelling halt. Fortunately for me, the Germans stopped and concentrated on our ball-turret gunner. That allowed me to escape. I guess they figured a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush,” he said.

All of the crew except the pilot, copilot and the ball-turret gunner huddled out of sight behind the barn. It seemed like hours that they waited and wondered what was going to happen to them.

“Finally some guy showed up with a rowboat in the nearby lake. It was getting to be dark and he took us on a boat trip around the lake,” Pogue said. “Eventually, he pulled into shore with his boat. We all got out and headed for a little stone cottage a short distance away.”

It was there that Pogue and the other members of the crew learned they had been rescued by the Dutch Underground.

“They gave us cigarettes and some awful-tasting schnapps that would blow the top of your head off with a single swig,” he said. “They also provided us with better fitting coveralls, like the farmers wore. They were trying to make us as comfortable as possible as we waited in the stone house for ‘The Chief’ to arrive.”

The pilot and copilot were hidden somewhere else by the Underground. The ball-turret gunner was by now in the clutches of the Germans. They flew one man short on this trip, so there were only nine aboard the B-17 when it went down.

“De Clerc was just an average-looking guy in his 40s. But he was one of the big names in the Dutch Underground,” recalled Pogue. “They called him ‘The Chief.’ He was a farmer who owned a fruit farm not too far away from where we were hiding.

“After he arrived, we all left on bicycles in the middle of the night. It was darker than a bugger, but we followed the leader on our bikes,” he said. A couple of Dutch policemen were leading the way. Most of the Dutch police were in the Underground.

“We reached another village, it was still night when they loaded us and our bikes into another rowboat and took us for another ride down a canal. After disembarking we rode our bikes for a while until we came to a German guard post along the road.

“The Germans wanted to know what was going on. Nobody was supposed to move around at night without permission from them,” he said. “The Dutch policeman, who was leading us, told the German guards, ‘We have some black marketers and we’re taking them to jail.’ The Germans let us pass.

‘About 2 a.m. we reached De Clerc’s fruit farm. We were given a little bread and cheese to eat and bedded down for the night in his place. About the time we woke up, a Dutchman came in with our copilot, who had been taken away from the bomber crash by a girl on a bicycle and hidden somewhere else.

“The Underground was on the radio all night long, trying to find out what Allied control wanted to do with us. The Underground was told they must find a way to return us to the Allies,” Pogue said. “That night things began to jell. The Underground found different safe houses for us to stay in for the time being.

“The navigator and I were taken by car to Hillegom, Holland, where we stayed in the attic of a young couple’s house who owned a tulip bulb farm outside town. For a month we lived with Jaan Lommerse and his wife, Gre, and their 18-month-old son.”

Problem was, there was a German contingent in the neighborhood building a gun emplacement along a nearby railroad track. Every morning the Germans would stop by the Lommerse’s farm to borrow tools to build the gun pit. It was risky business having American airmen in the attic with the Germans so close.

Even though the crew of the B-17 bomber “Straighten Up and Fly Right” was shot down in a raid over Germany they all survived the ordeal. 2nd Lt. Leonard Pogue is standing second from the right.

“You’d wake up in the morning in the attic and a German platoon would be marching down the road out front, singing their marching songs as they went,” he said. “They could really sing. But it was also an eerie feeling because you knew who they were and who you were and how close they were to you.”

Conditions for hiding U.S. airmen at the farm became too risky because more Germans arrived in the area. The farmer was becoming more and more concerned for the safety of his family. He complained to the Underground and they moved them out of there to a new hiding place in the village of Noordwyikerhout not too far away.

“We stayed at the home of a retired Dutch army doctor and his grown family who were all involved in the Underground operation.

“There wasn’t a lot to do except wait, play solitaire or read any available English book,” he said. “I read the New Testament twice because I had my little New Testament with me when we were shot down.”

It was February 1945 when the eight B-17 crewmen were moved again. This time they bicycled to a nearby canal and were transported in a cargo boat full of potatoes to Rotterdam, one of Holland’s major cities.

“We got there and our contact didn’t meet us. He had been caught and shot by the Germans. The captain of the boat we were on was frantic,” Pogue said. “Later in the day some guy showed up and took all of us to an apartment in downtown Rotterdam.

“Then we were scattered round in other safe houses in the city. For a while they were moved from house to house, eventually ending up with a 30-year-old woman and two guys who were part of the Dutch Underground resistance.”

When these two resistance fighters weren’t killing Germans, they were assassinating Dutch collaborators. It was a scary time for Pogue. Sometimes the two fighters would come back to the apartment with the barrel of their pistols bloody from people they just killed. At one point during a German sweep of the area they lived in, they were almost caught.

This picture of their B-17 was taken by a member of the Dutch Underground after they crashed in Nazi-occupied Holland. Photo provided

The B-17 crew escaped Rotterdam in a mail wagon with the help of the resistance and wound up in another boat – in the dark—being rowed with muffled oars by a Dutch “river rat’ to the 1st Canadian Army’s position down the river.

“As we were going down river in the dark, all of a sudden we heard this pit, pit, pit, pit, pit. It was a German machine gun firing in the dark at us.

“Fortunately, they couldn’t see us, so the ‘river rat’ pulled his boat up on the bank and waited until thing cooled off. Then he rowed on down the river again,” Pogue said.

“We reached the Canadians on March 18, 1945 and were taken to an improvised headquarters where we were given food, cigarettes and shots. At some point were turned over to the Americans and debriefed.”

The crew was sent back to England and, a few days later, left South Hampton, England for the United States.

“We arrived in New York City on May 7, 1945, the day before VE-Day and the German surrender,” he recalled. “I got a call from my wife, who thought I had been killed when our B-17 went down. Nobody held bothered to tell her I survived.

“I took a train from New York to Detroit and met Millie in a hotel in downtown Detroit on May 8. When she opened the door of her hotel room, she took one look at me and fainted.”

They met again

In 1995, half a century after the liberation of Holland from the Germans in World War II, the Dutch government invited the Allied airmen back for a big reunion. These old air crewmen were the guests of honor at an official government affair honoring them and the Dutch Underground who rescued them from the enemy.

“I thought I died and went to Heaven,” Leonard Pogue said. “You wouldn’t believe it unless you were there.

“My wife, Millie, and I and two other members of our crew attended the affair,” the Port Charlotte, Fla. man said. “They paid our way. We couldn’t spend a dime.

“You would have thought I had run the Germans off. I had nothing to do with it. It was the Canadian Army that ran the Germans out.

“The people of Holland loved us. They thought we were heroes. They had parades and celebrated with us for 10 days.

“They wrote a book about us and our adventures with the Underground. We even had a book signing. The only problem with the book is it’s in Dutch and I can’t read it,” Pogue said.

Pogue’s File

Name: Leonard A. Pogue

Name: Leonard A. Pogue

D.O.B.: 18 Aug. 1921

D.O.D.: 16 Nov. 2010

Age at time of interview: 82

Hometown: Bloomfield, Mich.

At the time of this interview: Port Charlotte, Fla.

Entered Service: August 13, 1942

Discharged: September 1945. Reserve commission until 1970

Rank: Captain Air Force Reserve

Unit: 493rd Bomb Group, 863rd Bomb Squadron, 8thAir Force

Commendations: Air Medal, EAME Theater Ribbon with bronze battle star

Married: Millie Mulligan

Children: Dr. L. William Pogue, Dr. Craig E. Pogue, Tracey Pogue Englebert

This story was first printed in the Charlotte Sun newspaper in 2003 and is republished with permission.

Click here to view the War Tales fan page on FaceBook.

B17 bomber flight brings back memories of WW II for local man

Charlotte Sun (Port Charlotte, FL) – Sunday, January 28, 2007

Author: DON MOORE; Senior Writer

When Leonard Pogue of Port Charlotte climbed aboard a World War II B-17 bomber called “Nine O Nine,” it could have been a scene from the ’40s movie “Twelve O’ Clock High” that began with a flashback on a weed-covered 8th Air Force bomber base somewhere in England years after the war.

But Pogue, 85, was at Venice Airport on Friday afternoon for a 30 minute flight to the St. Petersburg-Clearwater International Airport.

It’s not the first time Pogue’s been aboard a bomber — he was a bombardier on a B-17 named “Straighten Up and Fly Right,” which was shot down on Nov. 2, 1944, by enemy jets while making a bombing raid on German oil refineries at Merseburg.

His four-engine bomber crashed in Holland. All but one member of his crew, who was injured, was rescued by the Dutch Underground and returned to Allied lines months later.

On Friday, Pogue settled into the bombardier’s seat in the nose of the “Flying Fortress.” It was the first time he had sat in his old seat in more than 60 years. Back then he was a 20-something second lieutenant serving in the 493rd Bomb Group, 863rd Bomb Squadron, in the 8th Air Force stationed in Debach, England.

Friday he was an old man with a gray beard reliving a moment of his youth in a long-outdated bomber that helped bring death and destruction to Nazi-occupied Europe a lifetime ago.

The Collins Foundation’s “Flying Fortress” and equally impressive B-24 “Liberator” have become living history making their annual 134-city national tour.

At 2 p.m. “Nine O Nine” began rolling down the Venice Airport runway with all four engines screaming. Pogue was strapped in and seated on a floor cushion under a .50-caliber machine gun once used by a waist gunner to fend off attacking German fighters.

Shortly after the big bomber was airborne, the crew allowed the former bombardier and a Sun reporter and photographer to make their way to the plane’s nose, following Pogue on a winding route around equipment, across an 8-inch-wide catwalk spanning the bomb bay loaded with racks of dummy 500-pound bombs to the cockpit, through a crawl space under the pilot’s and co-pilot’s feet to the bombardier’s swivel seat in the plexiglass nose of the B-17.

“I didn’t recall how tight it was in that plane. I could hardly get from one end of the bomber to the other,” Pogue said. “When I was flying in one of them all the time, I would run from one end of the plane to the other with my heavy flight suit on, wearing a parachute, carrying an oxygen bottle at 20,000 feet or more with no problem. Not anymore.”

As he sat in the best seat in the house, he played with the highly classified Norden Bombsight he once used to make sure he hit his intended targets. Before him on this flight was the panorama of Florida’s Gulf Coast instead of the German military-industrial complex of six decades ago.

Flying in an aviation dinosaur 1,000 feet above placid Gulf waters, the B-17 crept slowly just off Siesta Key, Longboat Key and Anna Maria Island shorelines under a bright blue sky with white clouds in the distance. “Nine O Nine” swung a bit to the northeast as it headed over Egmont Key, site of the 1840 lighthouse built by Gen. Robert E. Lee at the mouth of Tampa Bay.

“As I was sitting there I kept looking over to my right to see if No. 4 engine was windmilling and if the No. 3 engine had been feathered. They looked OK, but I didn’t hear anything from the pilot so I wasn’t sure,” Pogue said in jest.

He could have closed his eyes at this point and conjured up his last mission. “Straighten Up and Fly Right,” his bomber, was shot out of the air by a German ME 362 jet fighter used by Hitler’s Luftwaffe in the closing days of the Second World War. The German jets were so fast, Pogue said, that most of the guns on his B-17 couldn’t track and shoot the fighters out of the sky.

With one engine shot to pieces and the other three barely operating, Pogue’s pilot tried desperately to keep their crippled bomber airborne long enough to ditch in the sea. He couldn’t do it and ended up plowing a farmer’s field in Holland with the battered airplane.

Eight of the nine-member crew escaped the crash, thanks to the Dutch Underground, minutes before a contingent of German soldiers arrived. Only the ball turret gunner was captured because he injured his knee and wasn’t able to run.

For the next four months Pogue and the rest of the crew were moved from home to home by the Resistance to keep them out of the enemy’s clutches. After escaping Rotterdam in a mail wagon and being rowed down a river in Holland in a small boat with muffled oars by the underground, they reached the 1st Canadian Army’s position and deliverance.

They were sent back to England and a few days later on to the United States. They arrived in New York City on May 7, 1945, the day before the Germans surrendered. Pogue never flew in combat again, his war was over.

Russian reporter gets earful of World War II stories

Don Moore; Senior Writer

Charlotte Sun (Port Charlotte, FL) – Thursday, August 30, 2007

It all began the other day with a call from American Legion Post 110 in Port Charlotte. I was told a Russian journalist had walked into the post looking for World War II soldiers to interview. Someone suggested getting her hooked up with me.

I made a date to meet Vicktoria Bazoeva at the Sun office the following day. In she walked in precisely at 9 a.m., looking like a tourist in her shorts, tank top and sandals.

After talking with her for a few minutes, I learned she is a junior at Moscow State University majoring in journalism. In her off-time, she works as a freelance journalist for papers and magazines in Russia.

She is spending two months in the U.S. interviewing World War II vets and taking their pictures as part of a collaborative effort with a photography professor. Together, they plan to publish a book called “The Heroes of the Real War.” It will contain short stories of individual soldiers who fought on all sides during the Second World War and their pictures.

“We’re asking each of the soldiers we interview what they remember of their service during the war,” Vicktoria said. “Our aim is to show that they were all just ordinary people who were caught up in the war.”

Toward that end, I took her to meet Leonard Pogue of Port Charlotte, a bombardier in a B-17 “Flying Fortress” called “Straighten Up and Fly Right.” He and his crew were shot down in a bombing raid over Merseburg, Germany, trying to knock out enemy ball-bearing and synthetic-oil plants.

The nine-man crew survived, however, their injured ball-turret gunner was captured by the Germans. Pogue and the other seven members of the bomber crew spent an eventful four months behind enemy lines ducking the Germans with the help of the Dutch Underground.

After her hour-long interview with the 86-year-old former bombardier, Vicktoria left apparently impressed with his war tale.

I got Vicktoria a second interview a couple of days later with an old submariner named Tom Moore. He lives in Eagle Point mobile home park on Burnt Store Road. He was a torpedoman aboard the USS Perch, the first American submarine sunk by the Japanese in World War II. He became a Japanese slave laborer on Borneo.

A few days after the Japanese bombed Manila, on Dec. 8, 1941, the Perch and its crew was on its second war patrol in the Java Sea. The U. S. submarine unfortunately surfaced at night next to an enemy destroyer that was floating motionless topside.

When the Perch’s skipper realized his error, he took his sub 240 feet to the bottom. More than a day later, the battered submarine was still resting on the bottom, three of its four engines had been blown off their motor mounts from the concussion of enemy depth charges, most of the lights aboard were shattered, and they were just about out of oxygen.

To make matters worse, the Perch was stuck in the mud and, try as they did, they could not extract their sub from the sticky bottom muck. It was at this point, one of the sailors suggested, “I think it’s about time for us to pray.”

Being a tough kid off the streets in upstate New York, it was something Moore wasn’t about to do. As the rest of the 60-man crew had their heads bowed, Moore just stood there until the cook realized he wasn’t praying.

Moore said, “Why should I pray. What has the Lord ever done for me?

“‘I’ll pray for you, Tom,'” the cook replied.

Moments later, all aboard the doomed sub heard a sucking sound. They stopped praying and listened. The sucking sound came once more. An instant later Moore recalled, “The stern of the boat started going up by itself. It was like a miracle.”

Everyone aboard realized they had another big problem. There was a Japanese destroyer waiting for them when the submarine surfaced.

The crew of the Perch experienced their second miracle a few minutes later. When the sub broke the surface, the skipper raced to the conning tower and discovered the destroyer had sailed away. The enemy skipper thought he had sunk the American submarine.

The ordeal for the Perch’s crew was only beginning. Since the sub hardly made it to the surface and was on the verge of sinking, the captain got the crew on deck in their life jackets. As they stood there at midday in the middle of the Java Sea looking toward the horizon, they spotted the entire Japanese fleet sailing their way. A short while later, an enemy cruiser started bombarding them with eight-inch shells as their sub sank under their feet.

After bobbing around in the sea, like ducks in a shooting gallery for the better part of an hour, they were taken aboard an enemy destroyer. Eventually the enlisted men wound up in a POW camp in Makkassar Celebes, Dutch East Indies. They built roads, airfields and worked on the docks for the Japanese. The officers were sent to Japan, and Moore never saw them again.

When Moore and the surviving members of the Perch were rescued more than three years later, he spoke fluent Japanese and fluent Malaysian. Asked how a teenager who lacked much formal education could learn to speak two difficult foreign languages, he told me, “You can do a lot of things you didn’t think you could do when you’re hungry.”

After listening to Moore’s war story, Vicktoria left the old sailor’s home with a smile on her face.

Really great article and Leonard, you are a hero to us all! Thank God for our freedom that you helped defend.

Love,

Letha

Letha,

Thanks for reading my “War Tales.” We put up three new stories a week and pictures to go with them. Hope you sign up for a free subscription at the bottom of any of the stories. Then you will automatically receive them on you own computer as they go up on Monday, Wednesday and Friday.

Regards,

Don Moore

Sun Newspapers

Hi, Thank you so much for this amazing story. I am Dutch and this makes me again so grateful to you special heroes. We all own you so much. We will never forget that because all of you we can live free. I posted a small article and direct link on our Dutch flightsim website. I hope this is oke. Greetings Matthias from simflight.nl: https://www.simflight.nl/2019/10/13/heel-bijzonder-en-iets-om-nooit-te-vergeten/