He flew The Hump 160 times – ‘I flew into the middle of a squadron of Japanese Zeros ‘ – Col. Baxendale

Lt. Col. Tom Baxendale of Port Charlotte, Fla. flew almost two dozen different military airplanes during his military career that spans World War II, Korea and Vietnam. Photo provided by Tom Baxendale

On one of the 160 missions he flew over “The Hump,” Lt. Col. Tom Baxendale ran head-on into a flight of Japanese Zero fighters. He was piloting an unarmed C-46 twin-engine transport loaded with 55-gallon drums of gas.

“I was flying from India to China, about halfway through the flight, minding my own business,” he said. “I flew out of the clouds into the middle of a squadron of Japanese Zeros. They were coming right at me. It was instant recognition.”

“I turned my airplane over and took it straight down into a bank of clouds below me. As soon as we got in the clouds, I changed directions,” said the 82-year-old, retired Air Force pilot who now lives in Port Charlotte, Fla. “I flew in the clouds for about five minutes. When we came out, we could see the fighters way off in the distance, going in the other direction.

“That was the last we saw of them. We turned toward base and hauled ass. I was in Burma on my way to China with a load of gas. We would have gone up like a torch if the fighters had caught us.”

Flying the Himalayan Mountains, the tallest peaks in the world, in a C-46 loaded with gas drums for the Chinese Army, in all kinds of weather both day and night took skill, luck and guts. It wasn’t a task for the faint-of-heart.

With a load on, the maximum altitude Baxendale could coax out of his two-engine transport was 21,000 feet. A few of the passes he had to fly through were 18,000 feet above sea level. That left little space to maneuver his plane.

To find their way, in some of the most terrible flying conditions in the world, all the members of the U.S. Air Transport Command had were beacons for a heading. Aviation was still primitive in those days. Many crews didn’t survive to see the end of the war. Their bones and the aluminum carcasses of their planes provide a testament to the courage of those who flew “The Hump.”

The Korean War

The Korean War was a repeat of Baxendale’s transport exploits during the Second World War. The major change between that war and the preceding one was that he was flying a C-54 transport. He could fly more people and cargo higher, farther and faster in the larger, four-motored airplane than he could in the two-engine, C-46 transport he had in WWII.

During the Korean conflict, he took people or supplies from Japan to Korea in 1951 and ’52, during the height of the war. Again, it was day and night flights in all kinds of weather. By then, planes had better radar, and flying conditions over the Sea of Japan weren’t usually as threatening as they were flying the Himalayas.

During the 23 years he served in the Air Force, from 1942 to 1965, he piloted 22 different airplanes. Trained as a fighter pilot, he spent his first two years attached to the Ferry Command, flying airplanes from the factory around the country to their point of debarkation. During that period, he jockeyed just about every plane the military was flying.

Baxendale flew P-51 Mustangs, P-47 Thunderbolts, P-38 Lightnings, P-36s, P-39s and P-40s. He also flew B-17 Flying Fortresses, B-24 Liberators, B-25s, B-26s, C-47s, C-54s and C-124s.

The old aviator is proud of the air time he’s logged flying into the Arctic to help build this country’s radar defenses against the growing Russian threat in the 1950s and ’60s. Off and on for a decade or more, he took all kinds of equipment and people to the frozen north country by transport. They were building “The Dew Line,” the United States’ radar defense system against attack from an enemy coming over the North Pole.

“At one time, I had more time flying in the Arctic than anyone else,” Baxendale said. “I probably had 1,500 to 2,000 hours flying up there.”

The ‘Lady Be Good’

On Nov. 9, 1958, a couple of British geologists flying over the sun-baked Sahara Desert some 400 miles south of Soluch, Libya, spotted a WWII B-24 bomber below them on the sand. Five months later, Baxendale flew Maj. Gen. George Spicer, commander of the 17th Air Force headquartered in Libya, to the site of the downed bomber in a C-47 twin-engine transport.

The story of the “Lady Be Good,” the bomber found in the sands of the Sahara, began on April 4, 1943, when 25 B-24D bombers of the 376th Bomb Group from Wheelus Air Force Base in Soluch headed for a high-altitude attack on Naples, Italy. The flight got caught in bad weather during the bombing raid. All but the “Lady Be Good” returned safely to base.

“Shortly after takeoff from Libya, the squadron commander’s bomber developed engine trouble. He turned his plane around and flew back to base,” Baxendale said. “The No. 2 bomber took over the flight and moved into his slot. He too had engine trouble and aborted.”

Then 1st Lt. W.J. Hatton, pilot of the “Lady Be Good,” took charge of the flight. According to Baxendale, the young lieutenant was flying his first combat mission. Apparently, none of the bomber crews on this Naples raid had much in the way of combat flight time. The oldest crewman in the flight was 23, Baxendale said.

Everything went OK on the first leg of the flight across the Mediterranean Sea to Italy. They were to fly over water paralleling the west coast, then turn east when they reached a point parallel with Naples and make their final bomb approach.

This is the only known picture of the ill-fated crew of “Lady Be Good.” They died in the Libyan Desert after their B-24 Bomber ran out of fuel and crashed on a combat mission during World War II. Photo provided

“The closer they got to land, the worse the weather got. It started raining and there was considerable fog. When the flight got over Naples, they couldn’t see their target so they diverted to a secondary target,” Baxendale said. “They dropped their bombs on the secondary target and headed back south toward their base in Libya.

“Flying in the dark on instruments with an 80 mph tailwind they didn’t realize they had, the crew of the ‘Lady Be Good’ got lost on the return flight. They overshot their base and ended up running out of gas in the dark in the Sahara.”

The entire crew of nine bailed out and apparently survived. So did their plane. It miraculously landed by itself and was in extraordinary condition when discovered 15 years later by the geologists.

The desert search

When Spicer got word the “Lady Be Good” had been found in his jurisdiction in the Libyan desert, he decided to fly there and check it out. He got his personal pilot, Baxendale, to take him on an expedition into the desert aboard a C-47 to inspect the old B-24.

“Gen. Spicer was a nosy-type guy. He wouldn’t have missed something like this for anything,” the colonel said.

Problem was, nobody Baxendale knew had ever landed a C-47 on desert sand. He wasn’t certain what would happen when they put the twin-engine plane down in the Sahara.

“I flew over the ‘Lady Be Good’ a couple of times before we landed,” he said. “The landing went fine. I got my two main landing gears down on firm sand. There was no extra drag on the wheels, so I gently let the tail wheel settle. Our plane stopped about 100 feet from the B-24.

“The plane was in beautiful condition, considering it landed itself. There was no signs of the crew,” the colonel noted.

The condition of the old bomber was good enough that they took a part from the plane’s radio and used it as a replacement part for their transport’s conked-out radio. It worked.

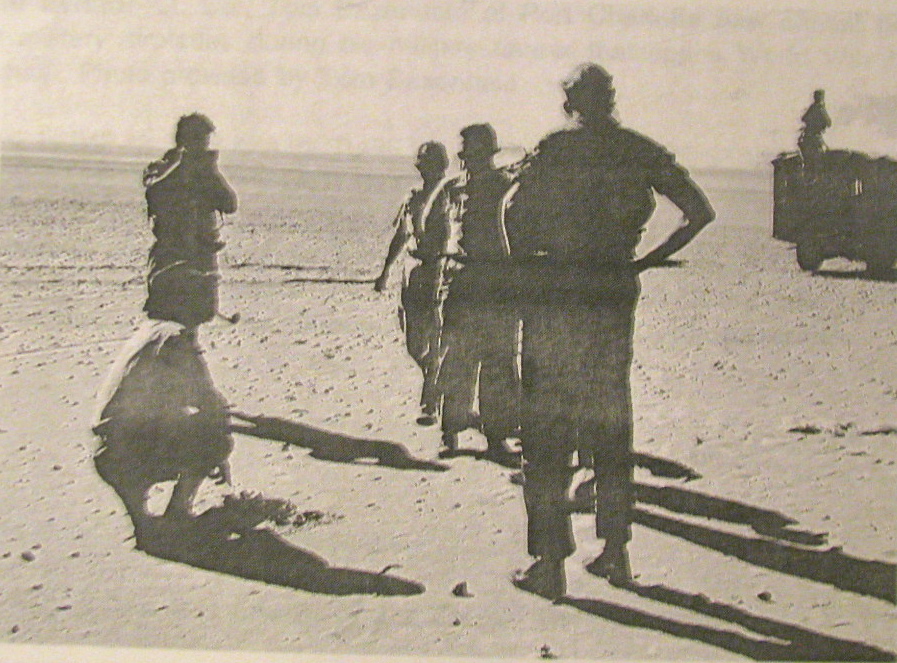

An Army grave registration unit had preceded the transport plane into the desert looking for the skeletons of the nine lost crew members. Baxendale and his crew hooked up with them and searched for some time by truck for the missing airmen, but found nothing. Finally, weeks later, the grave registration outfit located what they had been looking for.

A contingent of Air Force crewmen take pictures of the “Lady Be Good” after Baxendale landed a C-47 transport plane in the desert near by. He is the fellow in the center facing the camera. Photo provided by Tom Baxendale

According to the Web site http://www.wpafb.af.mil, in 1960, the remains of eight of the crew were found, one near the plane and the other seven far to the north. Five had trekked 78 miles across the tortuous sand before perishing, and one had gone an amazing 109 miles. In addition, they had lived eight days rather than only two expected of men in this area with little or no water. The body of the ninth man was never found.

To survive their ordeal, Baxendale said, they would have had to walk to the coast. It was 400 miles to the north of where the bomber went down.

‘Jack Kelley’

By 1961, the colonel was stationed at Leopoldville, Belgian Congo. He was serving as second in command of the American contingent there. One day he received a shortwave radio message for the American ambassador from Jack Kelley sent by Andrews Air Force Base near Washington, D.C.

“I’m talking to this guy from Andrews on the radio line at the airport, explaining that we’d try and patch him into the ambassador’s telephone,” Baxendale said. “But we didn’t have enough power for the ambassador to talk directly from his residence to Jack Kelley. So I relayed the messages between the ambassador and this fellow Kelley.

“The conversation between the ambassador and Kelley went on for 20 minutes or more. The ambassador would give me a message to pass on to Jack. Then Jack would respond, and I would tell the ambassador what he said.

“Toward the end of their conversation, I said, ‘Hold on for a minute, Jack. I just told the ambassador what you said. Give him time to respond.’ By that time, I was saying ‘Jack this’ and ‘Jack that.’

“When they finished, I pulled the plug on the connection and advised the ambassador. The ambassador said to me, ‘Major, do you have any idea who you were talking to?’

“‘Jack Kelley,’ I replied.

“‘I just want you to know, you’ve been calling the president of the United States by his first name,’ the ambassador said.

“I was shocked. ‘We got the enemy confused if they were listening in on this conversation,’ I said to the ambassador.

“‘How is that?’ he asked.

“‘No major in his right mind is going to call the president of the United States by his first name,’ I responded.

“He laughed.”

His commendations

Lt. Col. Tom Baxendale received the Distinguished Flying Cross, an Air Medal, two Air Force Commendations and 17 other awards during his 20-year Air Force career.

This story was first published in the Charlotte Sun newspaper, Port Charlotte, Florida on Wednesday, June 11, 2003 and is republished with permission.

All rights reserved. This copyrighted material may not be republished without permission. Links are encouraged.

Click here to view the War Tales fan page on FaceBook.

An incredible story! Thanks for posting this!