Jewish POW swapped by Germans in World War II

Pvt. Harry Glixon carries a German Luger pistol in his shoulder holster. He planned to sell the pistol to a buddy. Photo provided.

Harry Glixon couldn’t believe his ears when he answered the phone at his Sarasota, Fla. home one day in June 2001.

He wasn’t expecting to become a war hero after 57 years. The old soldier had been a member of a 55-man combat patrol from the 94th Infantry Division captured by the Germans near Lorient, France in the fall of 1944. He and his prisoner of war buddies were eventually part of the only POW exchange involving healthy prisoners made in the European Theater during World War II.

Glixon was about to play a role as one of a dozen veterans to participate in a tribute to A. Gerow Hodges, the young International Red Cross worker who conducted the exchange almost six decades ago.

Hodges, Glixon and the 11 other members of this very select group were honored at a testimonial dinner sponsored by Samford University in Birmingham, Ala. The school, which is also Hodges’ alma mater, is producing a television documentary about the prisoner of war exchange which it hopes will air on CNN and the History Channel.

“I was a radio operator. My captain thought the patrol might need some artillery support. Since I was also trained as an artillery spotter, he gave me a grease-gun (submachine-gun). I also took my 40-pound radio and was sent on my way.” Glixon said after returning from the affair in Birmingham.

The purpose of the patrol’s incursion into enemy territory along the Brittany coast was to capture a group of German officers who supposedly wanted to surrender to the Americans.

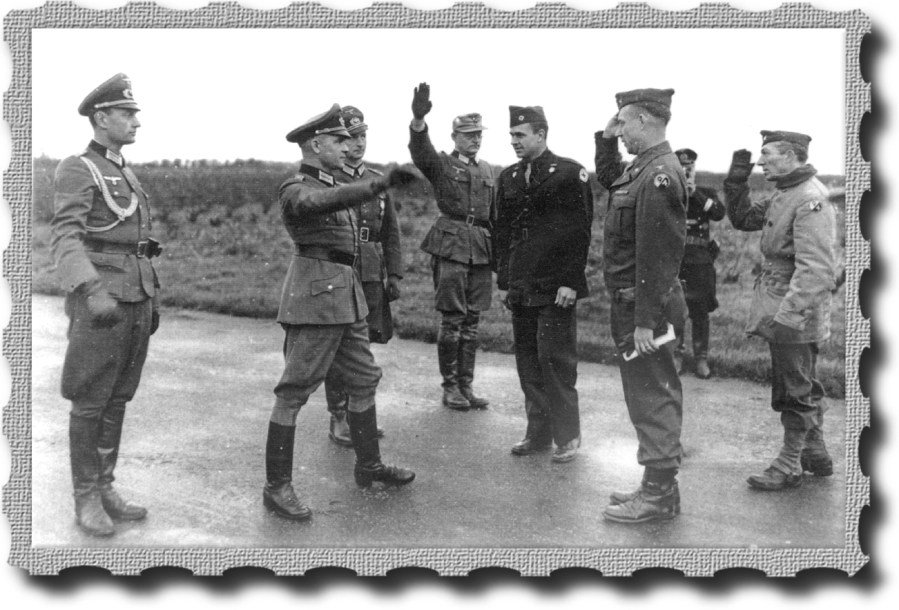

The officer giving the Hitler salute in the foreground was in charge of the POW exchange for the Germans. Andrew Gerow Hodges, the American Red Cross representative in the dark uniform in the center, set up the prisoner exchange in Brittany in November 1944. Pvt. Harry Glixon of Sarasota, Fla. was a member of the 301st Infantry Regiment, 94th Division of the 3rd Army who was exchanged by the enemy.

“At the time, our division was on the hills above Lorient overlooking the hedgerows below,” he said. “Shortly after moving out, we came to an open field. All of a sudden two shots rang out. Two of our scouts were hit.

“One died immediately, and the other was seriously injured. It was the first time I realized I could die in battle,” Glixon recalled.

It was Oct. 24, 1944, and the untested American patrol found itself pinned down by fire from battle-hardened storm troopers who held the high ground and watched their every move. The lieutenant who commanded the patrol told Glixon to call in artillery protection.

“I called in time-fire from our 105 howitzers,” he said. “There’s nothing like incoming rounds from a 105. With time-fire, the shells explode 30 feet above the ground, and shrapnel from the explosion causes terrible devastation.

“The Germans were highly trained. After the first couple of rounds, they realized what I had done. They knew their ass was in a sling, so they ducked. This gave us time to run for the protection of the hedgerows. I was scared out of my kazoo,” Glixon said.

Hedgerows were high bushes protecting the perimeter of almost every farmer’s field in that part of France. In between these protective bushes was a 6 to 8-foot wide dirt path.

“Once we made it to the hedgerows we hunkered down and returned the enemy’s fire. The men of our platoon were strung out for 150 yards along the path in a lousy position. We were still pinned down by the Germans,” he said.

A relief column was sent to rescue the beleaguered platoon, Glixon learned from his radio. It wasn’t long afterward he received a second call that the unit dispatched to snatch them from the jaws of death was also being attacked and fighting for its life. A few minutes later, headquarters radioed Glixon’s outfit it was on its own. The backup unit had been stopped by the enemy.

Members of the 94th Infantry Division, captured by the Germans at Lorient, France, stand in ranks during a funeral for one of their own held while they were POWs. Note the flowers on the crudely made wooden casket and the German officer standing at the far left side in the forefront.

“The Germans began dropping mortar fire on us. They were peppering us with mortars and our men were getting hurt. It was a horrible scene,” he said. “Our lieutenant got badly wounded.

“It was interesting the reaction of some of the people in our platoon when the going got rough,” he said. “I’ll never forget this guy who had been a real son-of-a-gun in basic training. During the whole time we were being attacked by the Germans, he was on the ground shivering.

“Other men in our platoon acted very bravely. One in particular, Pvt. John Atkinson, who took over for the sergeant, was the bravest of the brave.”

The two-hour fight between Glixon’s unit and the Germans became so frenzied the young American radioman called in artillery fire on his own position.

“Our colonel went into a fit when he heard I called in time-fire from the 105s on our position.’ I’ve got to do this to save the platoon from annihilation,’ I told him (by radio).

“He finally agreed,” Glixon said. “What I did was probably good, but it was done out of fear and revenge. Those bastards were gonna overrun us.”

Surrounded by the enemy, almost out of ammunition, their commanding officer seriously injured and not able to lead his troops, the badly injured lieutenant decided his squad had few options but to surrender.

Atkinson was ordered to hold up a white surrender flag the Germans could see.

“Unfortunately, he took a bandage out of his pack. He stuck it on his bayonet attached to his rifle and used it as a surrender flag. Atkinson walked out into the field of fire. As soon as he was in the clear, a German machine gun, about 50 yards away, opened up on him,” Glixon said. “Machine gun bullets cut him in half. It was one of the most horrible sights I’ve ever seen. John was a real hero.”

With their hands raised above their heads, what was left of the unit surrendered to the Germans a few minutes later. Being Jewish, Glixon got rid of his dog tags with an “H” stamped on it for Hebrew.

The Americans were marched off to Storm Trooper headquarters in Lorient for questioning.

“We were interrogated at great length by Lt. Schmitt, who was an arrogant but brilliant man. He had been a spy in Paris who spoke French better than the French. He also spoke very good accented English.

“He never did ask me if I was Jewish. But when he looked at my address book and saw Cohen, Ginsburg and other Jewish names, he smirked.

Andrew Gerow Hodges (right) is negotiating with Oberleutenant Dr. Alfrons Schmitt (left) and Oberst Otto Borst (center) for the release of the American POWs. The picture was taken on the quay at Etel, France on Nov. 16, 1944. Photo provided

“’When we capture a Jewish American’ —he drew his finger across his throat. “Be thankful we haven’t captured one yet,’” Glixon said the lieutenant told him. “It wasn’t a very good feeling.”

The next morning the American POWs were marched to a cemetery for the burial of four of their buddies. As the prisoners stood in ranks, their German captors held a military burial complete with wooden caskets, flowers and an honor guard that fired a rife salute for their fallen enemy.

“The German officer who conducted the funeral service spoke of valor, dedication bravery and the fatherland,” Glixon said. “At no time did the officer talk about death.”

After a few days in captivity, they were transferred to Ile de Groix Island, five miles off Lorient along the Brittany coast, where they spent the next month or so until their exchange. During this period food was scarce for POWs. Thanks to Red Cross packages the Germans allowed to get through, the prisoners survived.

In November 1944 Hodges, a young Red Cross worker was detailed to the 94th Infantry Division. His job was to see that food and supplies reached Allied prisoners of war in the Lorient sector.

He did much more. The 22-year-old social worker, who was 4-F because of a college football injury, took it upon himself to become a negotiator. With the blessing of his superiors Hodges convinced the German military authorities they should swap 149 American POWs for a like number of German prisoners.

“We started hearing rumors there was going to be a prisoner exchange. We were put in boats and taken back to Lorient,” Glixon said. “The artillery stopped firing for six hours and we were exchanged one for one and three for one if the prisoner was a sergeant.”

It was a formal affair. The soldiers to be exchanged were lined up in ranks facing each other. Officers from both sides were in the middle conducting the swap.

There was a lot of saluting. German officers were giving the Hitler salute with an extended arm. Their American counterparts saluted in return.

Film crews captured the event for the public both in the United States and Germany. It was a big deal for both sides from a publicity standpoint.

Within hours, on Nov. 15, 1944, Glixon and his fellow POWs were back in friendly hands. They were checked by doctors, and wined and dined. They expected to be sent home. It didn’t happen.

Since he had only suffered minor injuries in the firefight and lost only 20 pounds during his 45 days in captivity, Glixon was send back to the front lines with the 94th Division that was part of Gen. George Patton’s 3rd Army. His capture by the enemy a second time could have meant death. He would fight in the Battle of the Bulge and continue with his division on to march through Holland and Germany, and wind up in Czechoslovakia by the end of the war.

Harry Glixon and his wife, Lorraine, look at the book he wrote for his grandchildren and some old war pictures involving his time as a POW of the Germans during World War II. Sun photo by Don Moore

“I got a call last June from Herbert Grooms Jr., a trustee at Samford University, about the testimonial dinner in Birmingham for Mr. Hodges,” Lorraine, Glixon’s wife said. “Harry and I were asked to attend.

”I told him Harry had written a book about his World War II experiences. He wanted to see it, so I sent it to him.

“Mr. Grooms wrote back that Harry had written a very vivid portrait of battle. ‘There was nothing glorious about it – war was just plain hell,’” she said he wrote.

Grooms, a retired Marine colonel, also said in a note to Glixon, “I’d be honored to have you in a foxhole beside me. You’re a real hero.”

“We consider Mr. Grooms’ comments quite an honor coming from a Marine colonel,” Lorraine said.

Then Harry received a letter from the university saying the school was filming a documentary about Hodges, the Red Cross worker who brokered the POW exchange a lifetime ago, and they wanted to interview Harry as part of the project.

When the Glixons arrived in Birmingham for the affair last month, they were amazed at their reception.

“In addition to being the center of attention at a banquet for 300, we were treated to the original 15 minute Movie Tone News production of the prisoner exchange. The men were lined up like tin soldiers on both sides (in the old movie footage). It was a phenomenal experience,” Lorraine said.

“Four of the 12 men who came to the reunion were Jewish. This was a Christian college, but there was such an outpouring of love from everybody.” She said. “They were interested in their stories, in the POW exchange and what Mr. Hodges had done. They made us feel very, very important. It was just incredible.”

Glixon’s File

Glixon’s File

Name: Harry Glixon

Age: 82

Hometown: New York, N.Y.

Address: Sarasota, Fla.

Discharged: December 1945

Rank: Sergeant

Unit: 301st Regiment, 94th Infantry Division, 3rd Army

Commendations: Two Purple Hearts, Bronze Star with V for Valor, European Theater Medal, four campaign stars, Combat Infantryman’s Badge, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, Army of Occupation Medal with German Clasp, World War II POW Medal, World War II Victory Medal and Good Conduct Medal.

Married: Lorraine Finke

Children: Jill, Alan, Scott, Roy

This story was first published in the Charlotte Sun newspaper, Port Charlotte, Florida on # and is republished with permission.

All rights reserved. This copyrighted material may not be republished without permission. Links are encouraged.

Click here to view the War Tales fan page on FaceBook.

Click here to search Veterans Records and to obtain lost medals.</p

Harry Robert Glixon, Electrical Engineer, 86, died on December 10, 2007 at his home in Sarasota, Florida, of complications from Parkinsons Disease.

Before moving to Sarasota in 2003, Mr. Glixon lived in the town of Somerset, Chevy Chase, Maryland for 37 years. He was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and moved to the Washington area from New York in 1968.

During World War II, he served in the 94th Infantry Division and saw combat duty in France and the German Ardennes. On October 2, 1944, he was wounded in action, captured in an infantry combat engagement in Lorient, France and held as a prisoner of war on the Ile de Goix off the coast of Brittany, France. On November 16, 1944, through the efforts of the American Red Cross, Glixon became part of the only group of exchange prisoners during World War II.

He was awarded the Bronze Star with Oak Leaf Cluster and V for Valor and his first Purple Heart with Oak Leaf Cluster. He returned to action during the Battle of the Bulge, was wounded again and received his second Purple Heart and his Combat Infantry Badge. He also received the POW Medal, Good Conduct Medal, American Campaign Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with four Bronze Service Stars, WWII Victory Medal, Army of Occupation Medal with Germany Clasp, Expert Infantryman Badge and the Expert Marksman Badge with Automatic Rifle Bar.

After the war, Glixon received his electrical engineering degrees from New York University and in May of 1954 was awarded a license to practice professional engineering in the state of New York. Glixon was founder and president of Consolidated Avionics Corp. of Westbury, NY, which developed digital instrumentation for NASAS and, at the age of 33, he was elected to the Young Presidents Organization.

He was a Senior Executive at Sperry Gyroscope, a predecessor of UNIVAC and Unisys Corp. Before his retirement, he was a consultant to a number of key defense and health care contractors, both in the USA and Australia.

His first marriage to Muriel Nadel ended in divorce. In 1993 he married Lorraine F. Neufeld-Robson of Paterson, New Jersey. In addition to his wife, Glixon is survived by a daughter, Jill Glixon Myers of Silver Spring, MD, and sons, Scott (Denise) of Oakton, VA, Roy (Linda) of Ashton, MD and Alan of Queens, New York, and sons, Arthur Neufeld (Lois) of Fair Law, New Jersey and Daniel (Heidi) Neufeld of Marlboro New Jersey and 12 grandchildren: Jason Meyer, Deborah Neil, Danielle, Mitchelle, Julie, Corwin and Megan Glixon, Emily, Max, Becky, Dana and Bruce Neufeld and three great-grandchildren, Jessie, Matthew and Ashton Neil.

Mr. Glixon was a life member of the American Ex-Prisoners of War, Manatee Chapter Florida, Disabled American Veteras, 94th Infantry Division, Mid-Atlantic Chapter, Jewish War Veterans, Sarasota Chapter, the Institute of Electronic and Electrical Engineers and a member of Temple Emanu-El of Sarasota, Florida.

A memorial service will be held on Wednesday, December 12 at 2 p.m. at DANZANSKY-GOLDBERG MEMORIAL CHAPELS, 1170 Rockville Pike, Rockville, Maryland. Interment will take place at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors at a later date. In the near future, a Celebration of Life will be held at his late home in Sarasota, Florida.

Shiva will be observed at the home of his son, Roy Glixon in Ashton, Maryland. Arrangments are under the direction of Toale Brothers of Sarasota, Florida.A memorial service will be held on Wednesday, December 12 at 2 p.m. at DANZANSKY-GOLDBERG MEMORIAL CHAPELS, 1170 Rockville Pike, Rockville, Maryland. Interment will take place at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors at a later date. In the near future, a Celebration of Life will be held at his late home in Sarasota, Florida. Shiva will be observed at the home of his son, Roy Glixon in Ashton, Maryland. Arrangments are under the direction of Toale Brothers of Sarasota, Florida.

Published in The Washington Post on December 10, 2009

Great article and collections. Makes me proud. Thank you

Roy Glixon

Roy –

Your father was a super individual and a great story teller. You have every reason to be proud of him.

Regards,

Don Moore

War Tales

Sun Newspapers

An amazing tale that I never knew about. He was always a brave soul… and will always be remembered.

Thank you Alan. It took more than 5 years for you to read your father’s book and to acknowledge his war service. I was proud to be his wife and to have edited his book from 1995 until 2005 when he completed it. Those were difficult times while he was writing it because it brought many frightful and disturbing memories of the war years. Before he died on 10 December 2007 he was relieved that he had finally managed to tell his children of his past.

Don: When did you receive this info re: volunteers in the community? I tried to find more info about them, but it kept referring me to your newspaper article that you did after our return from Birmingham. I hope you are well and keep moving like a lot of us old fogies. Would love to meet you for lunch some day, is it in the cards? Lorraine

How can I get a copy of Mr. Glixon’s book?

I don’t know who you are, but you can contact me via Email if you are interested in his story. LG

Hi. My name is Eric Erickson. I became interested in Mr. Glixon’s story after watching “Thank You, Mr. Hodges” last night and reading this article. I have a degree in History and have always been intersted in the history of World War II, especially personal accounts. I don’t know how to contact you via email, but my email is ericcerickson@hotmail.com.

Never thought this